Online Dissent Navigating China's Great Firewall

Today, we conclude the series “Zone of Dissent: Spaces for Criticism in China from the 1980s to Now,” focusing on

The Report on Religious Freedom in Vietnam is published on the first Monday of each month. If you would like to contribute information to the report, please send it to tongiao@luatkhoa.org or editor@thevietnamese.org.

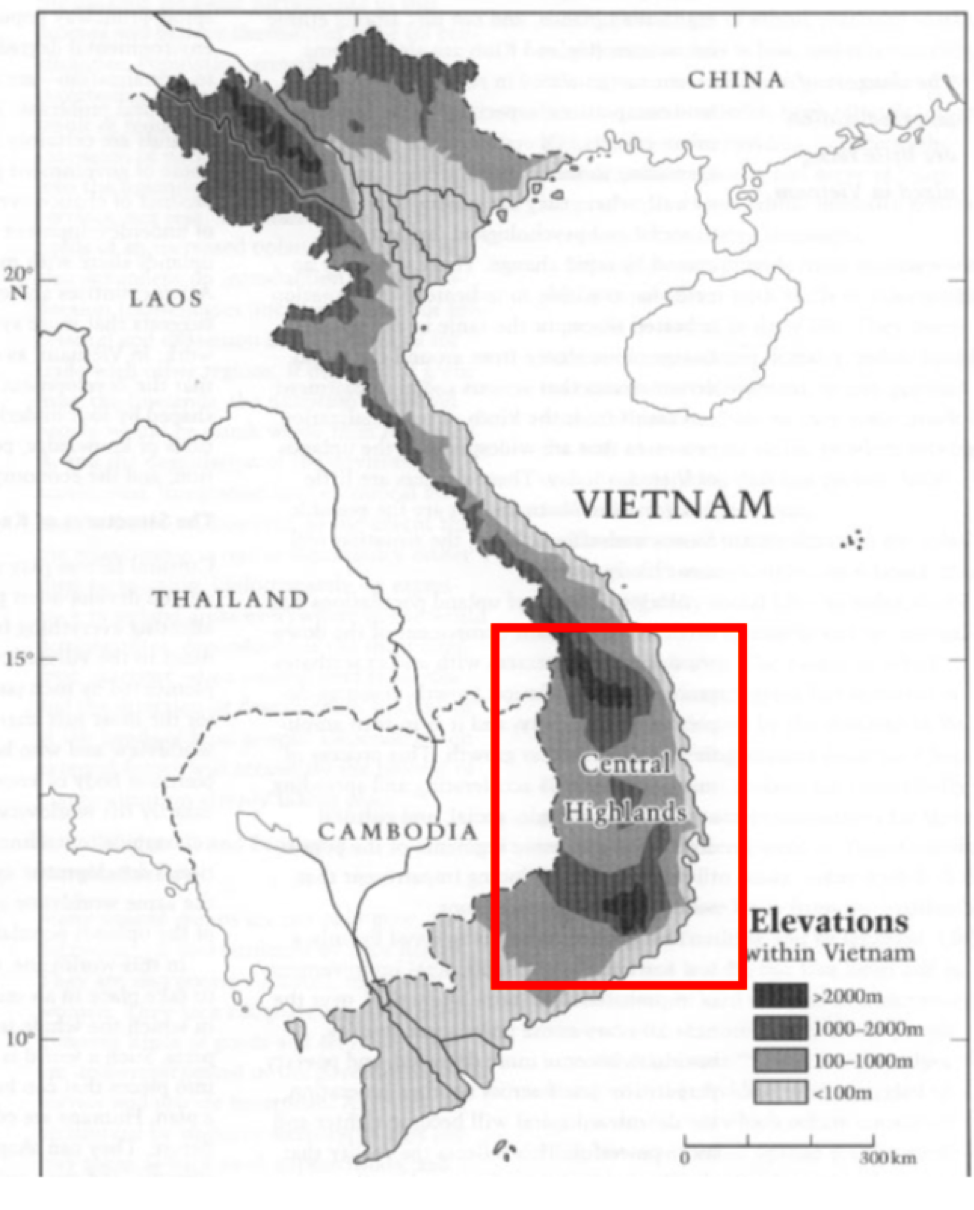

In this report, we will learn about the hotspot of the Central Highlands region in Vietnam where the government is intent on terminating FULRO (the United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races) and other new religions via [Religious HotSpot] and [The Government’s Hand]. Also, “The day the Honorable Master Huynh disappeared” and the current police tactics in suppressing this celebrating day will be discussed in [Religion 360°] and [On This Day]. In the [Did You Know?] section, you will receive some information explaining the history of the indigenous people in the Central Highlands.

The Central Highlands – Region:

· Area: 5.400.000 hectares

· Provinces: Kon Tum, Gia Lai, Dak Lak, Dak Nong, and Lam Dong

· Ethnicities: More than 30 (Indigenous groups and other ethnic groups migrating from the north of Vietnam)

· Population: 5.6 million in 2019

· Major religions: Catholicism and Protestantism

· New religions: Ha Mon, De Ga Protestantism, Montagnard Evangelical Church Of Christ, Buu Toa Three Sects, etc.

· Significant Issues: land rights, new religions and the right to autonomy.

· Popular criminal codes from the Penal Code 2015 are often used in prosecuting people regarding religious freedom: Sabotaging implementation of solidarity policies (Article 116), Activities against the people’s government (Article 109), Organizing, coercing, instigating illegal emigration for the purpose of opposing the people’s government (Article 120); Illegal emigration for the purpose of opposing the people’s government (Article 121); and Disturb public order (Article 318).

According to the Police Department in Ho Chi Minh City’s newspaper, on March 19, 2020, the Gia Lai police arrested three individuals who follow the Ha Mon religion who were hiding in the forest: Ju, 56,, Lup, 50, and Kunh 32. The Gia Lai police declared that these three people were suspects who escaped and continued to urge people to rise against the government.

These three arresteed men all come from Kret Krot Village, H’Ra Ward, Mang Yang District, Gia Lai Province. In April 2016, there were also two additional persons sentenced to 6 and 7 years in prison in a case involving five people who were connected to De Ga Protestantism.

According to the newspaper Nationality and Development, many people who lived in Kret Krot Village have joined Ha Mon religion since 2016. The government described the Ha Mon religion as based on the same beliefs as Catholics, except the followers do not worship in churches, which were places that the authorities allowed people to worship according to their religions. However, Ha Mon practitioners only worship at home in smaller groups. In 2012, there were more than 3,500 people from Bana and Sedang ethnicities practicing Ha Mon in three provinces, Gia Lai, Kon Tum, and Dak Lak. The government also categorized Ha Mon as a superstitious religion that would negatively affect the lives of the people since it would cause them to just pray and refuse to work. Authorities also designated this religion as destroying the national unity because the followers would force other people to practice the same faith.

More than that, the authorities also classified Ha Mon as a joint force with FULRO to rise against the government in Tay Nguyen.

During the past few years, the government continued its persecution of people who were deemed to be connected with FULRO in Tay Nguyen. In 2019, there were two individuals who were sentenced to 10 and 7 years in prison in Gia Lai Province. Furthermore, during the same time, the government also suppressed and harassed the followers of different religions that the government banned in the Central Highlands.

The harassment and torture of indigenous people in the Central Highlands by the government had caused many of these people to flee to Thailand for political asylum. At this time, there are more than 500 indigenous people from Vietnam’s Central Highlands currently seeking asylum in Thailand.

According to Political Analysis magazine published by the National Politics of Ho Chi Minh Institute, the government accused FULRO and De Ga Protestantism recently renewed their activism and with new religions, such as Supreme Master Qing Hai and Bo Khap Brau, they have organized strikes and probably even violent chaos in the future.

Central Highlands is located in a mountainous area of Vietnam, distancing itself from the rice delta. Since the Vietnam War, the Central Highlands has been an unsettled land where the indegineous groups did not accept the migration of the Kinh ethnic (the majority ethnicity in Vietnam) to the highlands. The migration of Kinh ethnicity after 1954 has caused the indigenous groups to lose their land and to have their culture assimilated.

FULRO was formed in the 1950’s to fight for the indigenous people’s right to autonomy in the Central Highlands, also for the Cham people in the coastal provinces in Central Vietnam and as well as the Khmer Krom in the south. However, this front was known for creating many significant conflicts in the Central Highlands before 1975, when it was fighting for indigenous people’s right to autonomy on lands, culture, and politics.

After the fall of Saigon in 1975, a few media reports stated that this front continued its fight with the new regime but later moved its operation to Cambodia to hide. In 1992, 400 people – who were the members of this front – were relocated to Western countries for political asylum.

According to Human Rights Watch, beginning in the 1980’s, the new regime in Vietnam continued a suppressive policy to eradicate religions while allowing massive migration to the Central Highlands. With an increased population, hunger and famine followed, effectively reducing the voices of the indigenous people.

“A lot of Montagnard people began to see that they were poor and underdeveloped. They felt that their lives were below the standards of those people who lived in the delta areas, the foreigners, and even the indigenous ethnic groups who came from the highlands in the north,” according to a special report in 1998 written by Neil L. Jamieson, Le Trong Cuc, and A. Terry Rambo. “The lack of money, food, and the right to receive natural resources, public access (to education, healthcare, information), these people face the risks of losing all of their most valuable resources: their confidence and dignity. They not only lack money and resources. In the end, the highlands area is always underdeveloped compared to the delta plain. The problem is that nowadays, there are more people who come to realize that they are poor.”

Until the 2000’s, demonstrations calling for religious freedom often happened in the Central Highlands. The authorities and their media outlets accused FULRO of organizing these demonstrations, using land rights and religious freedom to rise against the government. In the end, starting from 2004, the government also accused FULRO of organizing various groups to practice De Ga Protestantism and using religions to mobilize people to oppose the regime.

In the 1950’s, there were American missionaries who came to Vietnam and converted indigenous people in the Central Highlands to follow Protestantism. The indigeneous people practiced Protestantism along with the Catholicism that the French introduced earlier, but they also kept their traditional polytheism which was passed from generation to generation in the past centuries.

After 1975, the government classified religions and beliefs being practiced in Tay Nguyen as illegitimate because they were deemed to be superstitions just like other prohibited religions.

However, the number of people who followed Protestantism in Tay Nguyen increased dramatically, increasing by about 432 percent from 1975 to 1999 to 228,618 followers. While they were forbidden from practicing their religions, these followers gathered to practice their religious beliefs in locations far from the government’s watch. Beginning in the end of the 1990’s, the authorities started to allow the people to attend a few churches that the government allowed to operate. However, many others continued to practice their religion privately because they did not want to go to the churches that were organized by the government. Because of their poverty and a feeling that they were being suppressed, coupled with their petitions about land rights that were not being resolved, a few religious groups organized protests and demonstrated against the government in the 2000s.

Kpă Hung, 44, stated that he did not have any trust in the government. Kpă said that the government arrested him three times and the last time resulted in a 12-year-imprisonment in 2004 because he participated in demonstrations. “They tortured me and they said that was because I believed in Protestantism and Jesus Christ,” said Kpă, “and they would beat me up and torture me because they said that it was just like in the movies about Jesus Christ.”

“The day of protesting was just to have transparency, and to have the Vietnamese government correct its mistakes about corruption,” he said, explaining his reasons for joining the demonstrations in the 2000s. “But the government would never agree to change!”

Due to its geography and the control of the government, media and international observers could not access this area. The indigenous people of the Central Highlands who are currently seeking asylum in Thailand, have stated that every month, a few families escaped from there to Bangkok to apply for political asylum because the Vietnamese government suppressed their religious freedom or because they have lost their lands. The outdoor trials involving religions and FULRO are still widely happening in the Central Highlands.

In the past years, the government continued to maintain a harsh policy against indigenous groups. Any member of these groups that raised his or her voice to protest this policy in terms of the practice of religion without government approval would receive a heavy prison sentence.

During one of our investigations into the Vietnamese Montagnards living in Bangkok, Siu Wiu, a 43-year-old asylum seeker in Thailand, could still recall how he was sent to a re-education camp in 2004. At that time, he was being detained with 180 indigenous people from different ethnicities. In 2008, Siu Wiu kept encouraging people from his village to demonstrate to demand religious rights, land rights, and the release of indigenous people from prison. Siu Wiu was sentenced to 10 years in prison after this protest.

In 2017, Gia Lai Province prosecuted five people who were accused of receiving instructions from members of FULRO living overseas to conduct activities against the government. The authorities concluded that these five people were preparing to oppose the government’s great unity program. However, although the conclusion was that they only attempted a crime, the sentences given were very harsh. On April 5, 2017, the People’s Court of Gia Lai Province sentenced Rơ Ma Đaih, 31, to 10 years in prison, Puih Bop, 61, and Ksor Kam, 55, to nine years in prison, and Rơ Lan Kly, 58, and Rơ Lan Kly, 55, to eight years each.

During the last year, we have been gathering information on the most common tactics used by the government in its suppression of religious activities by religious groups that it does not recognize. We have also gathered details on how the government terminated activities that it deemed connected to FULRO in the Central Highlands.

Harassment and Suppression of People who Practiced Religion privately

Sen Nhiang, 34, of the Jrai ethnicity, escaped to Thailand in 2014 when the authorities in Ia Le Ward, Chu Puh District, Gia Lai Province, closed down a village church and arrested people who practiced their religion independently.

Before that, Sen practiced his religion privately with a group of people where he had to leave his house at 3:00 o’clock in the morning to avoid the police who watched his house. Police also surveilled his house, refusing to allow him to leave on the days he wanted to practice his religious belief and even on the days that he wanted to farm on his land. Sen was always afraid that the police would arrest him.

During the three months after Sen made his escape, the police often came to his house and threatened his wife, asking her to contact him and tell him to return to Vietnam. For many nights, the police also stayed over at his house and waited for him to come back as they thought he was hiding in the woods.

Also during the same months, three members of Sen’s group were sentenced to eight years, nine years, and 11 years respectively when they were found guilty of allegedly destroying the nation’s “great unity.”

Jen (the name was changed to keep this person anonymous) stated that his father escaped from Chu Puh District, Gia Lai Province, to Bangkok in 2013. In Vietnam, Jen’s mother was frequently questioned by the police because the government wanted to information about her husband. “Every month, they would ask me to go to the committee’s office, they assaulted me and they defamed me,” she said. “They questioned me about whether my husband would call me from Thailand or not, which vehicle he used, and what did he go to Thailand to do.” After Jen’s father escaped from Vietnam, Jen quit school because the school fees skyrocketed. There were also other women, who are currently living in the asylum center in Thailand also said that the police kept surveillance on their homes after their husband fled Vietnam.

In the asylum center in Thailand, many of the Vietnamese Montagnards do not have proper identification papers because the Vietnamese government refused to provide those to them. This is an effective punishment to those who continue to practice their religion independently.

When Sen Nhiang got married, he could not register his marriage. In the end, he was forced to pay 2 million Vietnam dong (approximately US$90) to the local committee to get the marriage certificate.

When they do not have identification papers, indigenous people are unable to travel far to work because they would not be able to follow the rule on registering for a temporary household registration. A lot of the people who are seeking asylum in Bangkok did not possess passports when they escaped Vietnam, and so had to pay from US$500 to US$1,000 USD to get out of the country illegally. This method is one way the government exerts its control over people and reduces their chance to leave Vietnam.

From our interviews with the indigenous asylum seekers who currently live in Thailand, we have learned that they were detained arbitrarily and tortured in different prisons.

Nay Them, 36, said that he was arrested and detained for 32 days in 2008 before the government released him. In the temporary prisons he was beaten until he was unconscious because the police wanted to force him to confess about his brother-in-law who had organized protests and who hid in the forest. Nay told us that the police of Phuoc Thin tied him to a chair and beat him with a log and also used a taser on him. The police beat him up many times before he was released.

Tay Nguyen is the highlands with mountains where many of the Montagnard villages are far away from the province’s financial districts and main cities, so that the people did not have connections with other human rights defenders to speak up about their arrests. For many years, Tay Nguyen is deemed as an unwelcoming place for foreign journalists. These were the reasons that the situation of arbitrary detention has not been mentioned in the news and also on social media.

After the demonstrations happened in the year 2000, the government continued to organize the “public guilt admission” meetings and used “outdoor trial” as its method to strictly warn the people to stay away from religious practice, not to escape Vietnam and also stay away from opposing the government.

On November 22, 2019, the police of Krong Buk District of Dak Lak Province organized a meeting to criticize people who they deemed to be in relation with FULRO in front of 300 residents in Cu Blang village, Pong Drang Ward.

On May 7, 2019, another “guilt admission conference” was organized with 150 villagers. At this conference, Kpa Nam, 36-year-old, admitted his guilt in public because he had joined FULRO and promised that he would not follow instructions from FULRO.

Kpa Nam was a person that was involved in the case of Rah Lan Hip, 39-year-old, and got accused of “damaging the nation’s unity policy.” Rah Lan Hip was tried in an “outdoor trial” on August 9, 2019 where he was sentenced to 7-year-imprisonment.

In 2013, The People’s Court of Gia Lai Province tried 8 people also in an “outdoor trial” where the defendants were accused of damaging the nation’s unity. In 2017, this court also sentenced 5 other people in another “outdoor trial”.

In the third Universal Periodic Review of Vietnam in 2019, the government accepted the recommendation from Denmark, calling to “abolish immediately at all levels the exercise of outdoor trials to ensure the right to presumption of innocence, effective legal representation and fair trials.”

In March 2020, a few Hoa Hao Buddhists organized a 73rd commemoration of the day their founder and master, Huynh Phu So, disappeared. The Hoa Hao Buddhists call this “the Day our Honorable Master disappeared”.

The followers of Hoa Hao Buddhism believed that their founder, Huynh Phu So, went missing on April 16, 1947, in Dong Thap Province during a meeting with the members of the Viet Minh Front – an organization that the Vietnam Communist Party formed in the south of Vietnam during the French occupation. The disappearance of Huynh Phu So has never been fully investigated, and some of the Hoa Hao Buddhists believe the Viet Minh assassinated him at that meeting.

“The day our honorable master disappeared” is one of the big three ceremonies of Hoa Hao Buddhism. After 1975, the new government prohibited followers from commemorating this day publicly, even though Hoa Hao Buddhism was recognized as an official religion in 1999. This commemoration is only recognized by the followers of the Pure Hoa Hao Buddhism Sect, a religious organization that is not recognized by the government.

The website of the Pure Hoa Hao Buddhist Sect announced that followers celebrated the commemoration in their homes in An Giang Province. The followers commemorated this day by decorating their ceremonial altars in their homes, preparing altars in their yards, and putting banners in front of their homes to prepare for the ceremony.

Even though the followers celebrated that day in peace, the police still set up posts to observe them and prevented followers from organizing the commemoration together. A member of the Pure Hoa Hao Buddhist Sect, Le Quang Hien, described how the police put up a post 500 meters away from the center of the sect to disrupt the travel of the followers on March 17, 2020.

In the end of February 2010, RFA reported that the police were involved in an altercation with local people who participated in a ceremony at Quang Minh Temple, which was an independent temple of Hoa Hao Buddhism. The participating members who came to the ceremony stated that they could not enter the temple because the police stopped them. This was the location where the yearly commemoration of “the Day the Master Huynh Disappeared” was often celebrated.

As RFA reported, on February 28, 2010,Tran Kim Long stated that the police assaulted him when he tried to enter the Quang Minh Temple. Long said that he recognized a few officers in that group who worked at the Cho Moi District Police Station in An Giang Province.

Vo Van Diem, the caretaker of the Quang Minh Temple, stated that on February 28 that followers and the police of Cho Moi District got involved in an altercation. Diem said that the police did not provide any written decision for the government forbidding followers to participate in the ceremony, only telling the followers that the government had not agreed to allow the people to have ceremonies in this temple.

In the same RFA news report, the news agency said that in a telephone call that the local police refused to answer RFA’s questions about the altercation while another police officer denied the incident happened.

In March 2014, when Quang Minh Temple was organizing the commemoration of “the Day Master Huynh Disappeared”, the police and followers again got into another altercation.

Vo Van Buu told RFA that he was assaulted by two strangers on March 25, 2014 when he was waiting for the bus after the police prevented him from entering Quang Minh Temple. Buu also said that a few days before, police stopped followers from entering the temple to prepare for the ceremonies.

Buu also stated that the police stationed forces in different areas to prevent followers from organizing themselves for ceremonies, such as in Long Giang Ward (Cho Moi District). The police also stormed Nguyen Van Vinh’s house seizing everyone’s cell phones and escorting people present there back to their homes, after which they refused to let them leave their houses. In Vinh Long Province, the police did not let Ha Tan leave his house. In Dong Thap, the police prevented Nguyen Van Tho from leaving his home on the “Day Master Huynh Disappeared.”

In 2016, also on this day of celebration, a few followers stated that they were beaten up by police, who blocked them from leaving their houses.

Le Cong Thu, a Hoa Hao Buddhist in Long Dien B Ward, Cho Moi District, An Giang Province, told RFA that on April 1, 2016 he was attacked by a group of people, including police, after traffic police stopped him to verify his papers while he was on his way to a ceremony commemorating “the Day Master Huynh Disappeared.” Thu also stated that during that same time, Tran Thanh Giang and Vo Van Buu, who lived in the same district as him, were harassed by strangers and had shrimp paste thrown at them.

On April 22, 2016, two other Hoa Hao Buddhists – Nguyen Ngoc Tan and. Nguyen Thi Lien, were stopped and attacked on their way home after participating in the commemoration at the house of another member of the Pure Hoa Hao Buddhist Sect.

How many indigenous ethnicities in Tay Nguyen?

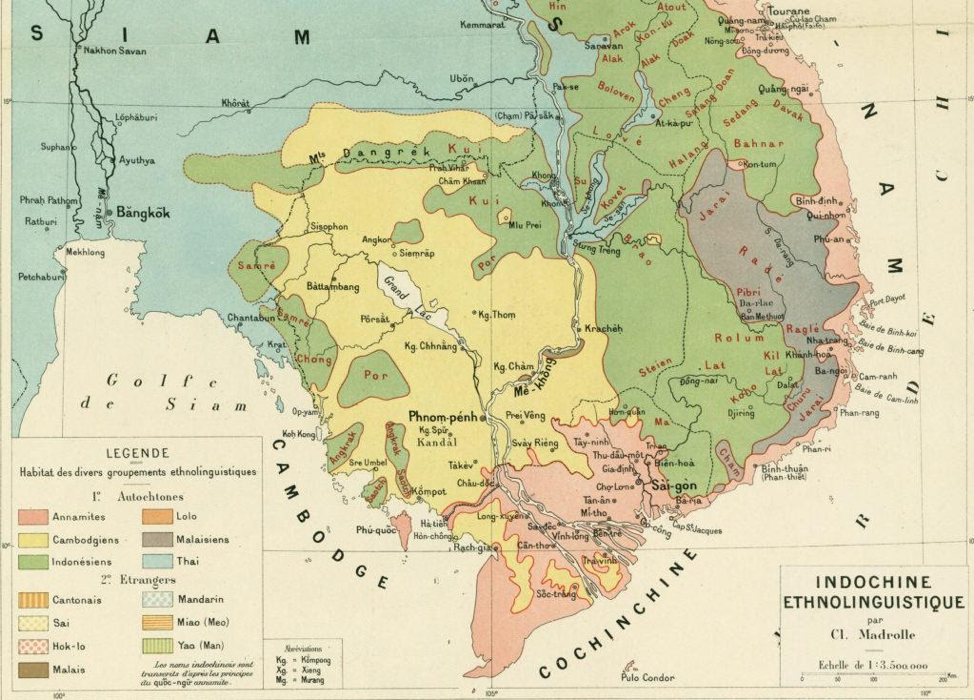

In the early 20th century, when the Central Highlands was still quite difficult to access,researchers believed that the indigenous population of this region was between 300,000-500,000 people, with three major tribes: Bana, Sedang, and Jrai. Moreover, there were also people of Lat, Ma, Stieng, and Sre in the Lang-biang Plateau and the Gia-rinh Plateau. The Mnong people also lived in the southwest part of Dak Lak Plateau and the northwest part of Lang-biang Plateau.[2]

Today, there are more than 20 indigenous ethnicities in the Central Highlands. Furthermore, there are other ethnicities that migrated from North Vietnam who now live in this region together with the indigenous people.

What is the ancestry of the indigenous people in Tay Nguyen?

There has not yet been an accurate definition for the ancestry of the indigenous groups in the Central Highlands. However, researchers agree that these ethnicities have been assimilated by the Cham people and become subsidiaries of the Champa Kingdom. They once lived along the coastal areas but later yielded to the Cham and moved to the high mountain of Truong Son in the Central Highlands.

A French researcher, Jacques Dournes, believed that the difficulty in accessing the mountainous area had caused the ethnicities to form their own languages just as the legend continued to be passed on. The indigenous people told Dournes that “many years ago, the ancestors spoke the same language, but eventually they could not understand each other anymore when they traveled far from each other.”

When the Cham people lost power, Vietnamese took control of the area, but the Montagnards still lived freely in their region. The mountains, forest, rivers, creeks, and animals still belonged to the Montagnards, who decided when they would pay tribute to the Vietnamese-Annam court. After the French arrived, this area was studied in more detail.

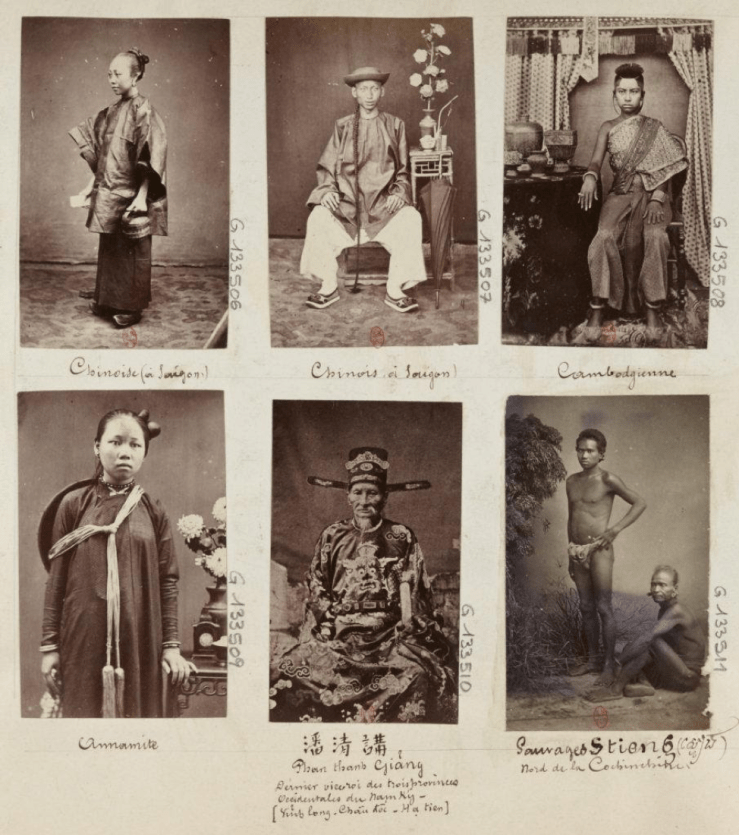

Why Were the Indigenous People of the Central Highlands Called Montagnards?

“Montagnard” which means “Highlander,” or “Mountain Man” in French, was the term that the French used when they colonized Vietnam to describe the indigenous people in the Central Highlands with more than 20 different ethnicities. These ethnicities had lived in the forests and mountains of the Central Highlands before the Kinh ethnicity (the majority ethnic group in Vietnam) set foot there. The Ede, Jrai, and Bana had a larger population than the K’ho, Sedang, Stieng, Ma, etc. After 1954, the Republic of South Vietnam continued to call these ethnicities Montagnards. Following 1975, the word “Montagnard” was no longer used, with the new government classifying these groups as “minor ethnicities”.

Which religions do the indigenous people of the Central Highlands follow?

For many generations, the indigenous peoples practiced polytheism, They believed that the many gods that they worshipped would protect them if they lived in peace with nature in the inhospitable mountainous area. All of the activities of the indigenous people here focused on their polytheistic beliefs, including childbirth, marriage, finding land to farm, harvesting, pandemics and death and funerals.

At the end of the 19th century, Western missionaries came to the Central Highlands where they hid from the Vietnamese court because promoting Catholicism was punishable by death. As such, the missionaries converted the minor ethnic groups in this area to Catholicisims, and so Christianity flourished in the Central Highlands during the French colonization. In the 1950’s, Protestantism became more popular in the Central Highlands when American missionaries arrived.

How many indigenous people follow Protestantism today?

According to Political Analysis magazine published by the Ho Chi Minh National Academy of Politics, in 2018, there were 450,000 indigenous people in the Central Highlands, with the migrating ethnicities from the north of Vietnam currently following Protestantism.

This is the number of followers who practice religions approved by the government, which consists of 1,665 groups, 300 sections, and 120 churches and praying centers. The minor ethnicities that practice Protestantism have significant numbers which include: E De (133,593), Gia Rai (82,604), Bah Nar (35,309), K’Ho (74,864), M’Nong (23,284), and Xe Dang (6,473).

Vietnam's independent news and analyses, right in your inbox.