Socialist Legality and the Paradox of ‘Self-Evolution’ in Việt Nam

A cursory examination of the fate of “socialist legality” (pháp chế xã hội chủ nghĩa) in Việt Nam reveals several

A cursory examination of the fate of “socialist legality” (pháp chế xã hội chủ nghĩa) in Việt Nam reveals several truths that Vietnamese communists would prefer to keep hidden. First, they have always been willing to “self-evolve” (tự diễn biến) to survive. Second, throughout this process, they have not hesitated to mechanically impose legal philosophies imported from Europe.

Consider a scenario involving a chaotic crowd of football fans. If one had only five seconds to capture the attention of a Vietnamese communist by whispering into their ear, what words would work?

“Corruption,” “deliberate wrongdoing,” “the blue license plates of government cars,” “Antigua & Barbuda passports acquired for safe havens,” or perhaps “Nguyễn Phú Trọng”?

However, there is another viable option: “self-evolution.”

While the phrase has existed for some time, it took on a more urgent and confrontational tone in October 2016, when the 12th Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam issued Resolution No. 04-NQ/TW.

The resolution’s core objective is to “prevent and roll back the degradation of political ideology, morality, and lifestyle, as well as manifestations of ‘self-evolution’ (tự diễn biến) and ‘self-transformation’ (tự chuyển hóa).” The Party explicitly threatens to discipline any collectives or individuals displaying these signs.

Among the nine identified manifestations in the resolution is the act of “refuting and denying socialist democracy and the socialist law-based state; demanding the implementation of a ‘separation of powers’ system and the development of ‘civil society.’” Denying the socialist-oriented market economy and the regime of public ownership of land.”

The concept of the “socialist law-based state” (Nhà nước pháp quyền xã hội chủ nghĩa)—which the Party champions in opposition to the “separation of powers”—is not new. It is the form of state chosen for Việt Nam in the new millennium, enshrined in Clause 1, Article 2 of the 2013 Constitution.

However, the concept first entered the national charter in 2001 through Resolution 51/2001/NQ-QH10. Prior to this, the 1992 Constitution merely stated that the nation was “a state of the people, by the people, and for the people,” with the term “rule of law” notably absent.

Where, then, did the “socialist law-based state” originate? It is a long story that begins with a concept already present in the 1992 Constitution: “socialist legality” (pháp chế xã hội chủ nghĩa).

According to John Gillespie (2010), a law professor at Monash University, “socialist legality” (pháp chế xã hội chủ nghĩa) is a core doctrine of governance under socialist ideology in Việt Nam. Gillespie identifies four defining principles of this system.

First is “party leadership,” which mandates that both the state and society must strictly follow the leadership of the Communist Party.

Second, the law is defined as the “will of the ruling class.” However, the law does not stand above the state; instead, it originates from it. In this system, the ruling class is the working class—workers, peasants, and intellectuals—with the Communist Party acting as its sole representative.

Third, the party and state retain the privilege of imposing policy over law. Consequently, when necessary, party or state policy carries greater coercive force than statutory law.

Fourth, individual rights must always yield to collective rights.

Fundamentally, socialist legality is a doctrine of governance through law. However, despite the high-minded rhetoric regarding human rights and law in the 1946 Constitution, the communists initially had no intention of governing by law. According to Gillespie (2005, 2010), this resistance stemmed from two key factors.

The first was a "culture of resistance" that grew out of years of fighting against French colonial rule. The revolutionaries aimed to dismantle colonial authority and its associated philosophies, including the respect for Western legal structures. Their efforts created an inertia that bred contempt for the rule of law.

The second factor was the profound influence of Chinese communist education. Top leaders such as Hồ Chí Minh and Trường Chinh had both undergone training within the Chinese socialist system. One prevailing view among scholars of Chinese communist thought was that the political and legal doctrines of the Soviet Union could not be mechanically applied to East Asian societies, which were defined by deeply rooted village-based cultures and rigid social hierarchies.

To embed communist ideology into everyday life, Chinese communists believed it necessary to translate it into the moral language of Confucianism—a language familiar to East Asian societies like China and Việt Nam for thousands of years. Consequently, according to Gillespie (2004, 2005), post-1945 Vietnamese leaders chose “virtue-based rule” rather than law as their primary tool of governance.

Under this system, cadres acted as “role models” rather than legal administrators, relying on personal relationships and moral superiority to manage society. This focus on moral leadership and the “just cause” became a staple of Hồ Chí Minh’s writings.

However, Mark Sidel's 2008 research suggests that this model faced opposition. Internal debates saw figures such as Nguyễn Hữu Đang, Nguyễn Mạnh Tường, and Vũ Đình Hòe advocate for the rule of law, though this faction ultimately lost.

Change only arrived through crisis: the Land Reform campaign (1953–1956). Guided by the Chinese Communist Party, this virtue-based, directive-driven campaign resulted in a policy catastrophe. Thousands died—including Việt Minh supporters—and a culture of lawless denunciation fractured society, threatening the Party's legitimacy.

The situation was so dire that Hồ Chí Minh wrote a public apology. On Oct. 29, 1956, General Võ Nguyên Giáp also publicly acknowledged these errors at the Hanoi People’s Theater.

According to Gillespie (2004) and Bui (2014), this collapse of the Chinese-style model forced the communists into their first “self-evolution.” Desperate for a new governance model, they turned to Soviet experts who offered the solution: sotsialisticheskaya zakonnost—socialist legality.

This concept was ideal for the Vietnamese communists. It established law as a tool of the proletarian dictatorship to defeat enemies and protect the revolution, yet it maintained Party supremacy. The Party retained the power to define the “will of the ruling class” and override law with policy when necessary. Thus, fifteen years after independence, northern Việt Nam finally adopted law as its primary instrument of governance.

Gillespie (2005) offers a strong critique of how Vietnamese communists “imported” socialist legality, describing the process as mechanical and devoid of reflective thinking.

According to Gillespie, this rigidity stemmed from communist ideology itself, which prevented lawmakers from adapting Soviet doctrines to local conditions. Marxist-Leninist thought rejects the idea that law is culturally contingent; instead, it assumes—almost utopianly—that an egalitarian proletarian culture can erase local differences.

Furthermore, policymakers were constrained by a deference to the “big red brother.” They believed Soviet socialist thinking was correct, or at least, they wouldn't admit it was wrong. This fraternal ideological bond allowed Việt Nam in the 1960s and 1970s to adopt Soviet doctrines without the hesitation that later generations would feel toward “Western thought.”

As a result, Gillespie contends that the communists aimed to "reshape society to conform." They attempted to reshape Vietnamese society to align with imported laws, rather than adapting those laws to suit the existing societal context.

This mechanical style of legal transplantation persisted for decades, continuing even when Việt Nam later imported market-oriented laws to attract foreign investment—though that is a topic for another article. Despite its rigidity, this model of socialist legality and its four principles dominated the legal system from 1960 until the next crisis emerged.

By the 1980s, rigid Soviet-style economic management and dwindling ideological aid had plunged both the Soviet Union and Việt Nam into crisis. At the Sixth National Congress in December 1986, the Communist Party of Vietnam acknowledged these failures and launched Đổi Mới.

However, Đổi Mới revealed that the old doctrine of socialist legality—where law represented only the “will of the ruling class”—was incompatible with a multi-sector economy and private capital. Foreign investors demanded stability, predictability, and limits on state power. The law needed to be transparent and immune to the Party's sudden whims.

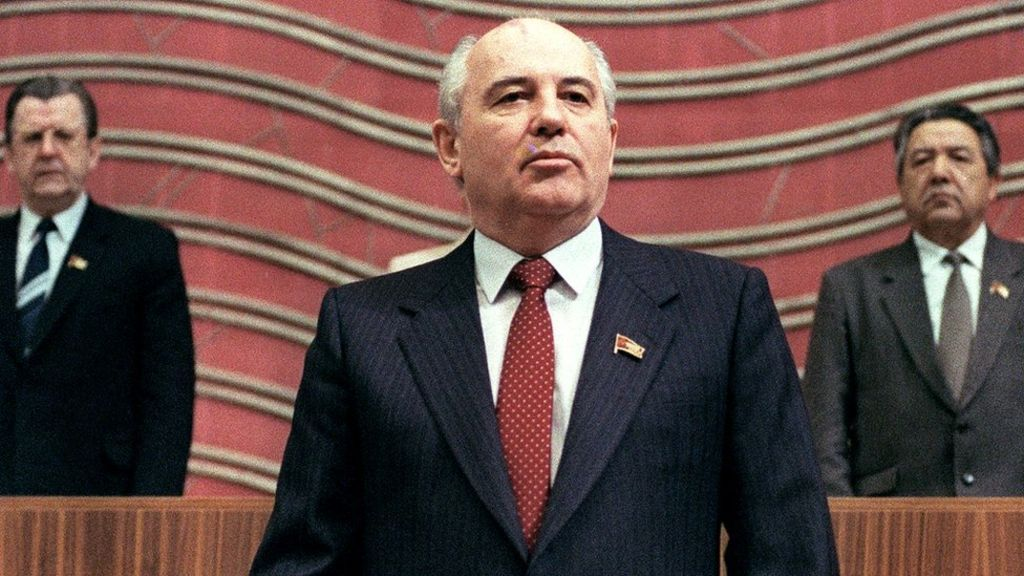

While often hailed as visionary governance, Đổi Mới legally represented a second episode of “self-evolution” and another mass importation of foreign ideas. To support these reforms, policymakers looked again to the Soviet Union, specifically to Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika. There, they found the concept of pravovoye gosudarstvo.

Under Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union introduced perestroika in the mid-1980s, partially liberalizing economic and social life.

Derived from the German Rechtsstaat (a concept of 19th-century Prussian absolutism), pravovoye gosudarstvo differs from the Anglo-American "rule of law." It does not rely on natural law. Instead, it elevates the role of statutory law: the Party sets goals, but the state implements them within legal constraints.

This concept effectively performed “cosmetic surgery” on socialist legality by separating party and state functions while maintaining party direction. It was the perfect hybrid to reassure the party while satisfying investors.

Uncharacteristically, the Vietnamese communists did not mechanically adopt this importation. They went further than the Soviets by fusing the two concepts to create a unique construct: the "socialist law-based state" (Nhà nước pháp quyền xã hội chủ nghĩa).

Here, “law-based state” is drawn from pravovoye gosudarstvo, while “socialist” retains the core of socialist legality. The state must obey public laws, yet must also follow the Party line—even if, as implied by leaders like Nguyễn Phú Trọng, Party rules conflict with the Constitution.

Formally introduced at the Seventh Party Congress in June 1991, this concept was added to the Constitution in 2001 and enshrined in 2013.

After 58 years and a significant “cosmetic surgery,” socialist legality has evolved into the “socialist law-based state,” becoming one of Việt Nam’s most revered constitutional principles.

However, 21st-century communists appear weary of this constant importation and adjustment of foreign legal philosophies. This exhaustion explains Resolution No. 04-NQ/TW and the mobilization of commentators ready to attack foreign political or legal thought.

To the Party, the history of socialist legality is an inspiring bildungsroman—a story of clever adaptation for survival and governance. However, from the perspective of an ordinary citizen, an important question remains: by banning “self-evolution” and “self-transformation,” is the Communist Party trapping itself in a perpetually changing world?

Early communists possessed a startup mentality, willing to learn from any model that worked. In contrast, today’s cadres, despite having access to the world’s knowledge, choose prohibition. Ultimately, they have chosen to ban “self-evolution” to protect their existence.

Nam Quỳnh wrote this article in Vietnamese and published it in Luật Khoa Magazine on Feb. 06, 2018. Đàm Vĩnh Hằng translated it into English for The Vietnamese Magazine.

Vietnam's independent news and analyses, right in your inbox.