Việt Nam 2025: 50 Years of Reunification, Celebration, and Unhealed Wounds

2025 marked a significant milestone for Việt Nam, commemorating the 50th anniversary of national reunification and the 80th anniversary of

Lê Giang wrote this article in Vietnamese and published it in Luật Khoa Magazine on August 12, 2025. Đàm Vĩnh Hằng translated it into English for The Vietnamese Magazine.

In recent years, Vietnamese society has inched ever closer to the threshold of an “aging population,” marking an unprecedented demographic shift in the nation’s history. This new phase officially began in 2011, marking the end of the era of the “golden population structure.” According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Việt Nam is now among the fastest-aging countries in the world.

The UNFPA defines a country as “aging” when people aged 60 and over make up 10% of the population, and an “aged society” when that figure reaches 20%. The data shows Việt Nam is approaching this second threshold at an alarming speed.

The national aging index also rose sharply from 35.5 in 2009 to 56.9 in 2018. As reported by Nhân Dân on June 6, 2023, by 2019, those aged 60+ accounted for about 11.9–12% of the population; by Feb. 9, 2023, that figure had surged to nearly 17%, or more than 16.18 million people.

At its current pace, Việt Nam is forecast to become an “aged society” in just 17–20 years—a transition faster than that of developed nations like Japan or Germany. By 2050, the elderly are expected to exceed 25% of the population. Faced with the looming risks of social upheaval and labor shortages, the critical question is: what policies has the State implemented, and are they sufficient?

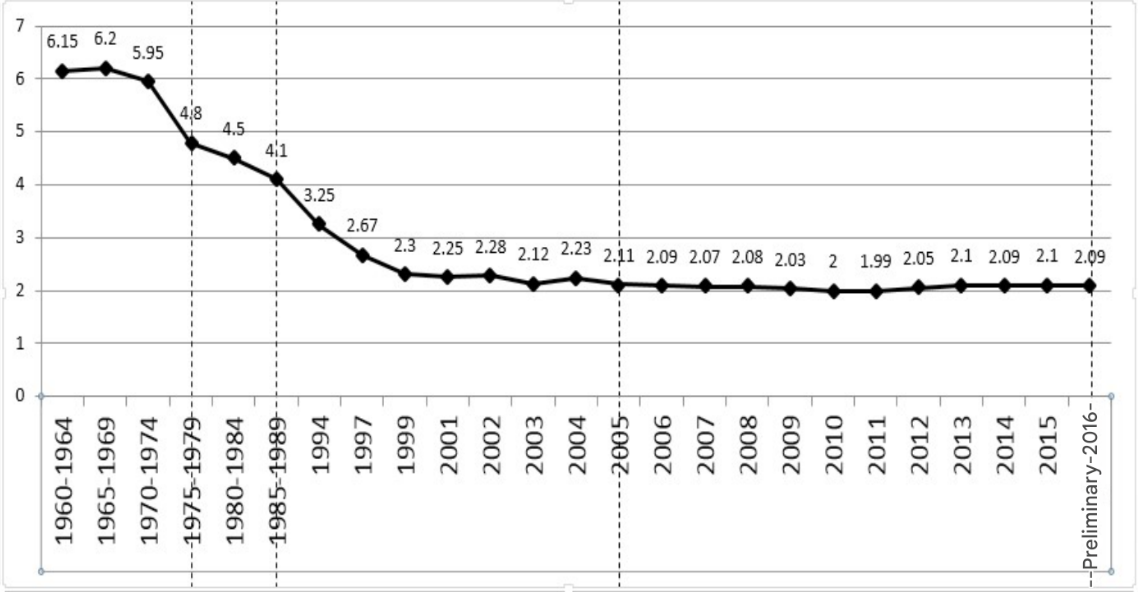

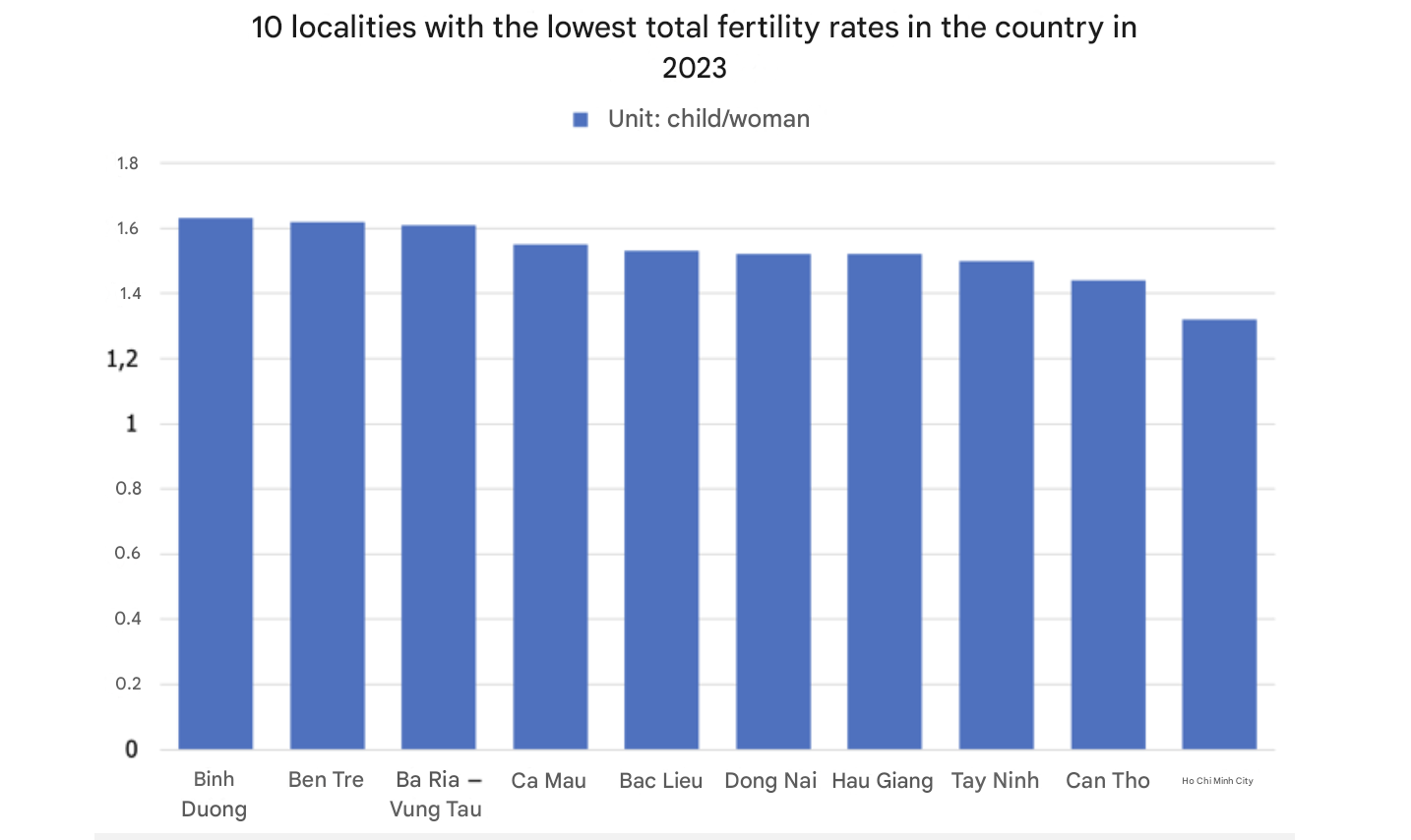

Việt Nam officially entered an alarming phase of declining fertility in 2022. At a rally for World Population Day on July 11, 2025, Minister of Health Đào Hồng Lan stated that the total fertility rate (TFR) had dropped to a historic low and is expected to keep falling. The TFR fell from 2.01 children per woman in 2022 to 1.91 in 2024, with the decline being especially sharp in major urban centers like Hồ Chí Minh City (1.32) and across the southern provinces.

Government officials point to several causes. Demographically, a key driver is the rising age of marriage. But this is fueled by a host of socio-economic pressures. As Deputy Director of the General Department of Population Phạm Vũ Hoàng cited at a policy workshop, these include: “urbanization, economic development, pressure to find jobs, housing costs, higher living expenses, rising costs for raising and caring for children, and infrastructure shortcomings such as school shortages, high tuition and medical fees, and lack of incentives for childbearing.”

This trend has dire implications for the country's future. Lê Thanh Dũng, a senior official at the General Department of Population, explained the projection in an interview with Dân Trí: “At the current low fertility rate in 2024, average population growth is 0.90%. It will drop to 0.68% by 2029, then just 0.06% by 2054. From 2059, population growth will turn negative.”

The long-term consequences of this demographic shift are severe:

Recognizing that encouraging childbirth is a complex issue tied to jobs, income, and housing, the Vietnamese government has implemented a flurry of new policies. These measures can be grouped into several key areas.

First, there are direct incentives and programs to encourage childbirth. Decision No. 588/QĐ-TTg, approved on April 28, 2024, aims to adjust fertility rates by urging young people to marry before 30 and by supporting families with two children in some cities. The draft Population Law 2025 goes further, proposing over 5.3 trillion đồng for pro-birth policies, including cash support for women having two children before age 35, subsidies for families with only two daughters, and much more.

Second, the state is expanding leave and social insurance benefits. The Ministry of Health has proposed extending maternity leave to seven months for a second child. As of July 1, 2024, men are now eligible for longer paternity leave (up to 60 days). The revised Social Insurance (BHXH) Law 2024 also provides more benefits for female workers, including special support in cases of fetal loss, maternity benefits for those undergoing infertility treatment, and a one-time maternity allowance for surrogate mothers.

Finally, there has been a move to broaden reproductive rights. A June 2024 amendment to the Population Ordinance now allows couples and individuals to decide the timing and number of children based on their own circumstances. In a significant shift, a July 2025 decree now allows single women to use assisted reproductive technology (ART), a right previously restricted to infertile couples.

Despite the recent flurry of pro-birth policies, the Vietnamese government's primary focus remains economic development, often through regulations that further limit livelihood opportunities. With the “real estate bubble” unresolved and the tangible effects of the new benefits still unclear, a question arises: are these measures genuine solutions, or merely political displays of benevolence?

According to Matt Jackson, the UNFPA’s representative in Việt Nam, the real barriers to parenthood are the immense economic and social pressures young people face. He cites a long list of obstacles, including high housing costs, lack of childcare services, job instability, and growing fears over conflict and climate change.

Jackson argues that the government is asking the wrong question. Instead of focusing on “How do we get women to have more children?”, the real question should be: “What barriers prevent individuals and couples from having the number of children they desire, and how can we remove those barriers?”

Ultimately, as UNFPA experts contend, Việt Nam must go beyond short-term incentives. The only sustainable path forward is to remove deep structural barriers—tackling child-rearing costs, workplace inequality, and domestic workload burdens—while investing in human capital to make the most of its remaining “golden population” opportunity.

You can read When the Cost of Living Becomes Birth Control in Việt Nam - Part One here.

Vietnam's independent news and analyses, right in your inbox.