A Teacher’s Reflection on Loyalty, Love, and the Story “Làng”

Đan Thanh wrote this article in Vietnamese, published in Luat Khoa Magazine on July 3, 2025. First and foremost, I

Contrary to rumors, when the North Vietnamese soldiers captured Saigon on April 30, 1975, it did not result in an immediate "bloodbath." Nevertheless, the tragedy experienced by the southern Vietnamese unfolded gradually and in different forms.

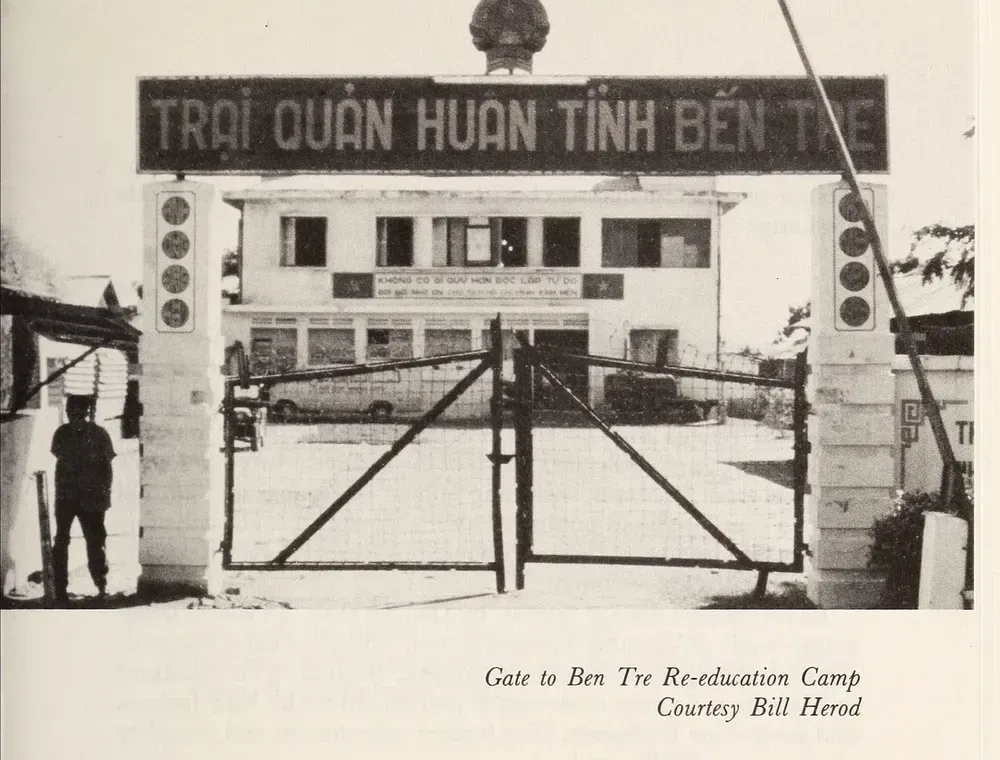

One day in June 1975, Colonel Tran Van packed his clothes, some food items, and money to attend the new government’s re-education program, which they claimed would be just a month-long class for former officers and soldiers of the Republic of Vietnam (RVN). [1]

On the first day, Tran Van and the other officers were well-fed and went to bed at 10:00 p.m. But at midnight, everyone was awakened. They were separated into groups of 40 people and herded onto trucks. About 100 such vehicles quietly left Saigon to go to an old camp of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) in the north of the city, which had just been turned into a detention area for the defeated soldiers.

Half a year later, they were transferred to another prison more than 60 km from their old camp. They heard officials say the new government would not let them return to their families because they had a "blood debt to the people."

Tran Van was later transferred to another re-education camp in North Vietnam, near the Chinese border. At this point, he heard the announcement that he and his fellow prisoners would have to earn money to provide for their own food because the state did not have the extra money to feed the officers and soldiers of the former RVN government who were being held in prisons.

For years, these former officers and soldiers of the RVN lived on a diet of cassava root and had to go to the forest to work daily from 5:00 a.m. They didn't know when or if they could return home.

In 1980, the Communist government admitted that it had forced more than one million people in the South to undergo short-term re-education camps and imprisoned more than 40,000 people for long periods without trial. [2]

In 1988, the deputy minister of information (later the Ministry of Information and Communications) confirmed that there were about 100,000 former soldiers and civil servants of the Saigon government imprisoned in re-education camps. [3] International sources later claimed that approximately 200,000 people had been detained around the country for at least a year. [4]

Colonel Tran Van was released after 12 years in a re-education camp. He was one of the lucky survivors.

Former South Vietnam politician Tran Van Son stated that during the two months he was detained at Dong Gang re-education camp (Khanh Hoa Province), about 100 re-education prisoners died from a lack of food and illness without any medical treatment. [5]

A doctor in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam was informed by the new government that his re-education period would be 10 days, but in the end, he went away for nearly three years. During the first 10 months of detention at the L11 Re-education Camp near Bien Hoa, according to this doctor, five people committed suicide, and 16 people died from malnutrition and lack of medical treatment. [6]

Another former re-education prisoner witnessed the trial of a captain and a lieutenant from the RVN Special Forces at a re-education camp in Tay Ninh. During the trial, two coffins were placed next to them because they were executed on the spot immediately.

Why were the Southerners pushed into re-education camps after 1975? What happened inside these places? Were only the soldiers and former Saigon government employees being detained?

Immediately after April 30, 1975, the new regime organized "re-education" courses for soldiers and civil servants of the former Saigon government, but its intention was unclear to the public. In fact, the re-education courses, which were claimed to be for just several months, turned into years of hard labor. [7]

In March 1977, Hanoi Radio reported that about 5% of former government military officers and civil servants had to go to long-term re-education camps. [8]

According to an article published by the Associated Press on Oct. 21, 1984, there were an estimated 100 re-education camps across the country, where about 150,000 soldiers and civil servants of the former regime were detained without trial. [9][10] However, they were not the only people locked up in re-education camps.

In addition to soldiers and civil servants of the RVN, many other groups, including those not involved with the Saigon government, were also arrested and sentenced to re-education camps.

In 1975, a trader in Buon Ma Thuot was detained and sent to a re-education camp for nearly three years for owning a store. [11]

In August 1975, 20 rice traders from Bac Lieu Province were arrested and sent to a re-education camp. Some of them were said to have been tortured to death. By 1979, four years later, some of these traders were still detained. [12]

Amnesty International stated that between 1976 and 1977, many people who had nothing to do with the former government were also arrested and sent to re-education camps, such as writers, artists, and civil servants who had retired before 1975.

By 1978, many Chinese businessmen were arrested and sent to re-education camps because of Vietnam's "anti-bourgeois campaign." [13] In addition, those who attempted to cross the border illegally or who failed to escape by boat could be forced into a re-education camp for up to three years. [14]

In 1980, AP reported that 200 Catholic priests were arrested since 1975, including Bishop Nguyen Van Thuan in South Vietnam. In addition, more than 50 Protestant pastors and more than 30 Theravada monks in the Mekong Delta were still being detained in re-education camps. [15]

In 1985, the Ad Hoc Committee for Vietnamese Political Prisoners in the United States said that there were about 300 writers, poets, and journalists still imprisoned in Vietnam. [16]

Some writers, who also had been RVN soldiers, were imprisoned for a long time. For example, To Thuy Yen served 13 years in prison, Phan Nhat Nam served 14 years in prison, and Thao Truong served 17 years. [17]

These harsh sentences underscore the reasoning behind the new regime's establishment of re-education camps: to isolate officers, soldiers, and southern elites from the general population, thereby preventing the emergence of any opposition forces.

The Communist government gave many different reasons for the necessity of the re-education camps to detain people in the South after 1975.

In September 1980, Hanoi stated there were about 20,000 people detained in re-education camps at that time. Without holding any trials or evidence, the government charged them with "betraying the Fatherland" and "harming public security." Vietnamese officials claimed the re-education policies were more humane than holding trials. [18]

After seven years of maintaining the re-education camps, in 1982, Foreign Minister Nguyen Co Thach announced that Vietnam was ready to let all re-education prisoners go to the United States unconditionally. [19] But just two years later, , Vietnam clashed with Washington over this policy. It wanted the United States to immediately accept all prisoners without having the option to reject any cases. [20]

A short time later, Vietnam asked the United States to ensure that these prisoners could not form opposition political forces after moving to America. [21]

Responding to the U.S. media in 1985, veteran diplomat Le Duc Tho said Vietnam was holding about 10,000 political prisoners in re-education camps at that time. Tho claimed that they were war criminals, not simply collaborators with the old regime. He said these people had not shown they had been reformed, and so they were still detained. [22]

However, a foreign diplomat believed that the imprisoned were elite officers and politicians of the South. The reason the Communists had not yet released them was that they were worried these individuals still influenced people in the South. [23]

Due to the lack of trials, re-education camp prisoners had no sentences or set detention periods. The Communist government could detain someone if it saw that the individual had political and social influence over people. The authorities could then detain such people indefinitely.

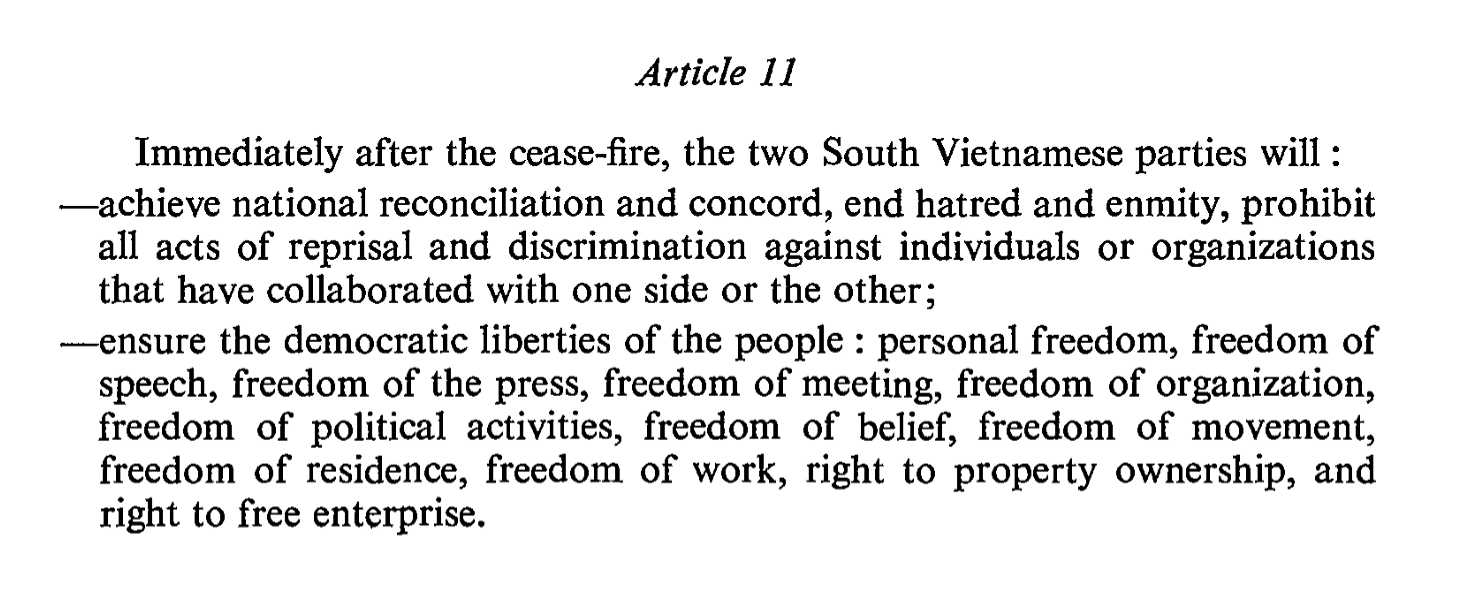

Refusing to implement the 1973 Paris Peace Accords and reconciliation policies, the new government harshly detained the former RVN officials and soldiers as political prisoners, forcing them to do hard labor.

The giant prisons established in Vietnam after 1975 were a convenient way for the government to eliminate some prisoners, as well as to punish people affiliated with the old regime or those who were suspected of having opposed the new regime.

Specifically, what did the Communist government do in these re-education camps?

Maj. Khong Nang Hanh, former commander of an ARVN artillery battalion, had all his teeth edentulated after 10 years of being detained in a re-education camp located in the North. He told a reporter for The Leader-Post at a refugee camp in the Philippines in 1986: “It was the most cruel prison camp. We didn't have anything to eat. We only got rice one day a month. For the remaining days, they fed us white radishes, potatoes, and corn." [24]

Another ARVN major said that of about 1,500 prisoners in the re-education camp in the then Ha Nam Ninh Province (now Kim Bang District, Ha Nam Province), where he was detained, about 15 people died each week from starvation and diseases. This situation lasted about two years before the authorities allowed prisoners to receive food and medicine from their family members. [25] The re-education camp in Ha Nam Ninh was also where Professor Nguyen Duy Xuan, former president of Can Tho University, was detained. Xuan passed away in 1986 in the camp due to a serious illness.

One prisoner said that during the first year in the re-education camp, the only food they ate was wild animals they managed to capture, such as snakes and lizards. By the second year, no animals were left to eat; the prisoners ate anything that lived on the ground. [26]

After two years in a re-education camp, a man's weight might only be about 36 kg. [27]

The living conditions at each re-education camp were often different. Prisoners most likely only ate white rice and salt, with very little vegetables and meat in their meals. Prisoners always felt weak, but they still had to do hard labor. [28]

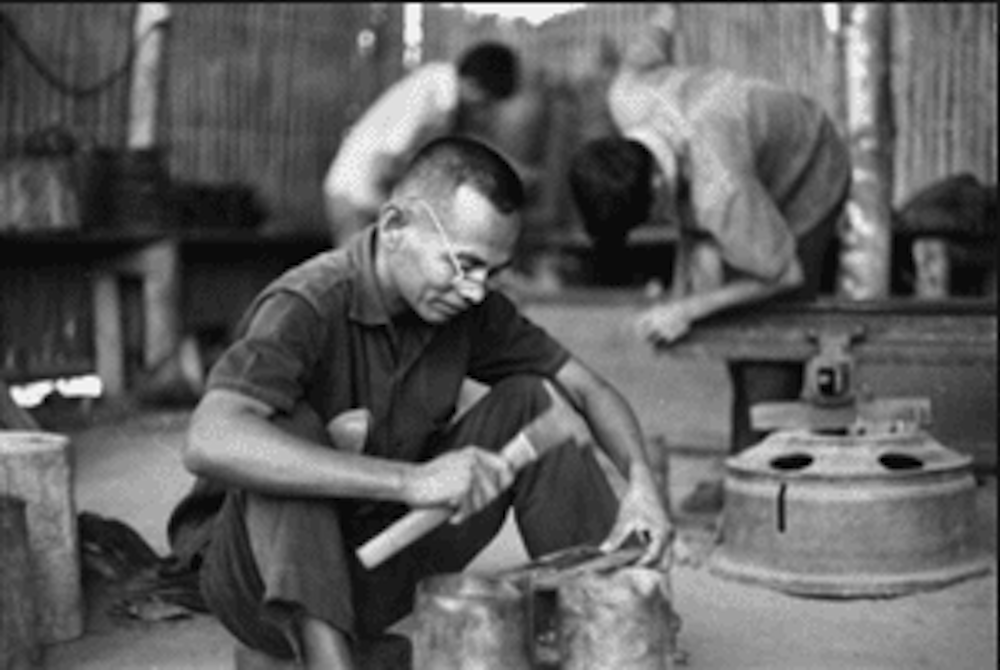

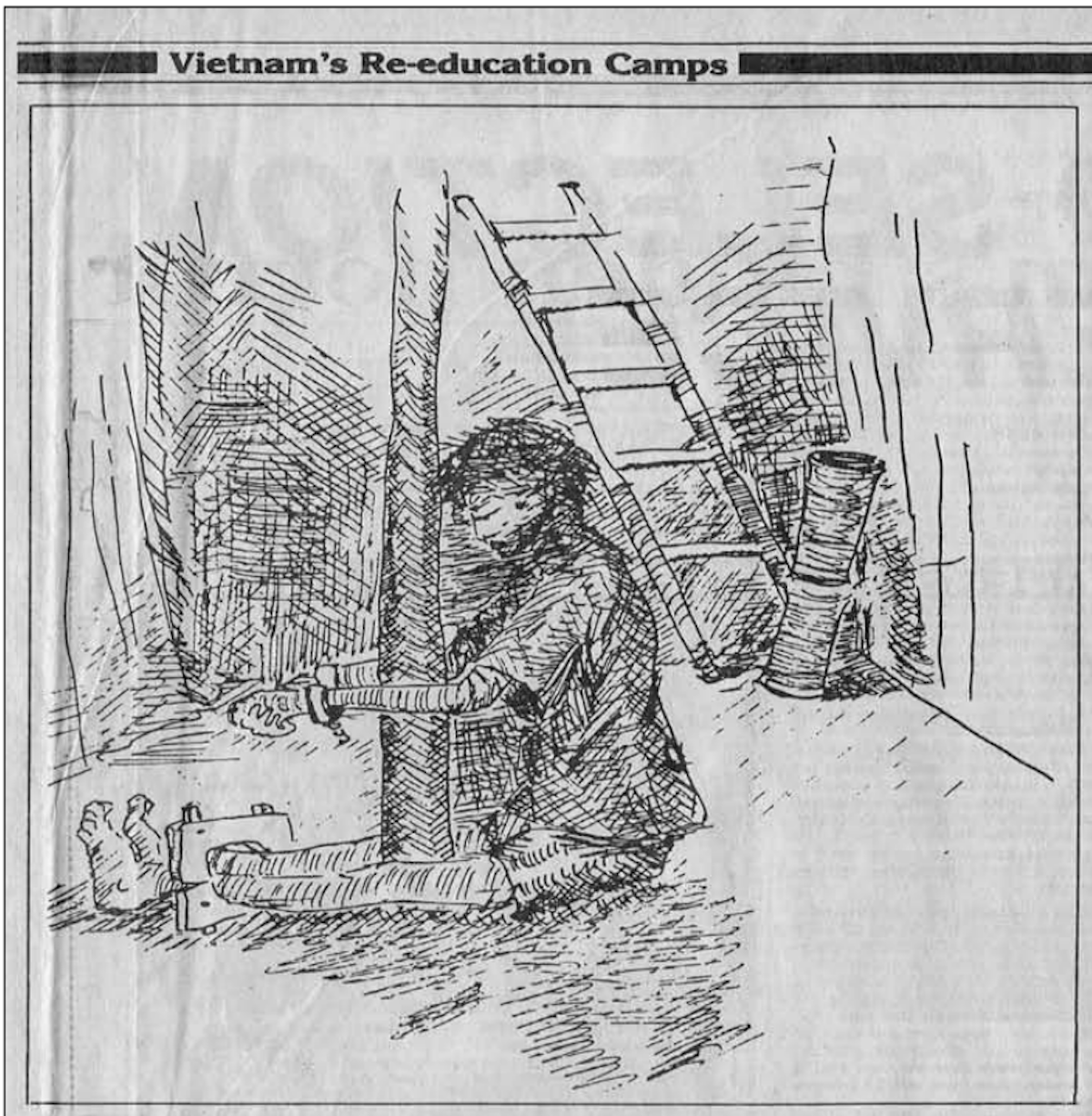

In the re-education camps, southern prisoners had to do heavy manual work all day long using their hands and rudimentary tools without any machinery.

A former prisoner recalled that they were given a rice ball every morning and then started working. For one month, they dug a 10-meter-long canal every day, and then the next month, they had to cut one cubic meter of wood a day. [29]

The prisoners had to do everything the prison guards ordered them to do, including cutting trees, roofing, and building houses for one guard after another. [30] A former re-education camp prisoner even stated that he was assigned the job of bringing human feces to fertilize the vegetable garden at the re-education camp, and officers forced him to use his bare hands to handle the feces. [31]

Lieutenant General Nguyen Huu Co, who once was the deputy prime minister of the Republic of Vietnam, was forced to dig ponds and cut trees from the forest to set up his own dwelling at a re-education camp in Yen Bai.

He was detained for 12 years and went through five different re-education camps. In the first few years, his family was not allowed to visit him, but later, he was permitted to see his family once a year. [32]

Death while working in the re-education camps was not a rare event. A former re-education camp prisoner said he was ordered to work in an old minefield left over from the war, where he said that many prisoners lost their lives or became maimed when they stepped on mines. [33]

But that was not the worst.

Incidents of denunciation were not rare under the Communist regime. At the re-education camps, prisoners had to declare a detailed life history of themselves and their families, including events from birth until 1975, and especially any connection to the United States.

In an interview with The New York Times, former National Assembly member Col. Tran Ngoc Chau, who was a prisoner at a re-education camp near Long Thanh, said he was forced by officials to rewrite his detailed biography twice, which had to include how he was manipulated by the "American imperialists." About a quarter of the people in his cell also had to rewrite their life history for a third time. [34]

Afterward, Col. Tran Ngoc Chau was forced to publicly discuss with other prisoners the “crimes” he had committed. These struggle sessions lasted for months, running from morning to afternoon, from afternoon to evening, with prisoners only allowed small breaks to eat and exercise.

Second Lt. Nguyen Van Thang recounted that the Phu Yen re-education camp officials forced him to rewrite his biography and insisted that he had to account for his family for three generations because he was a Catholic and had migrated from the North to the South in 1954.

The accounts of these life histories quickly turned into the lengthy guilty pleas by these prisoners. Many even had to make up their crimes because the prison guards told them that if a prisoner confessed to having committed more crimes against the revolutionary fight of the North, that person would soon be allowed to return home. [35]

Furthermore, in some re-education camps, prisoners manually worked during the day and had to study Communism at night.

Some re-education camp inmates said they were never beaten or tortured during their detention. However, many others recalled witnessing prison guards beating or shooting dead prisoners who tried to escape.

Former Lt. Pham Ngoc recalled that he witnessed one incident in which some 100 prisoners escaped the camp, but that up to 90 were killed immediately. [36]

Pilot Nguyen Van Trong recounted that six prisoners in his group were shot dead by camp officials because of a misunderstanding. One day, about 150 prisoners were led out by the guards to bathe in a stream. On the way, the prisoners in the front row needed to drink water, so they got permission from the guards (who were in the front row) to let them into a residential house to drink water. However, the guards following behind them did not know about this. So when these prisoners left the line, the guards behind them fired their machine guns and killed them, thinking that they were trying to escape. [37]

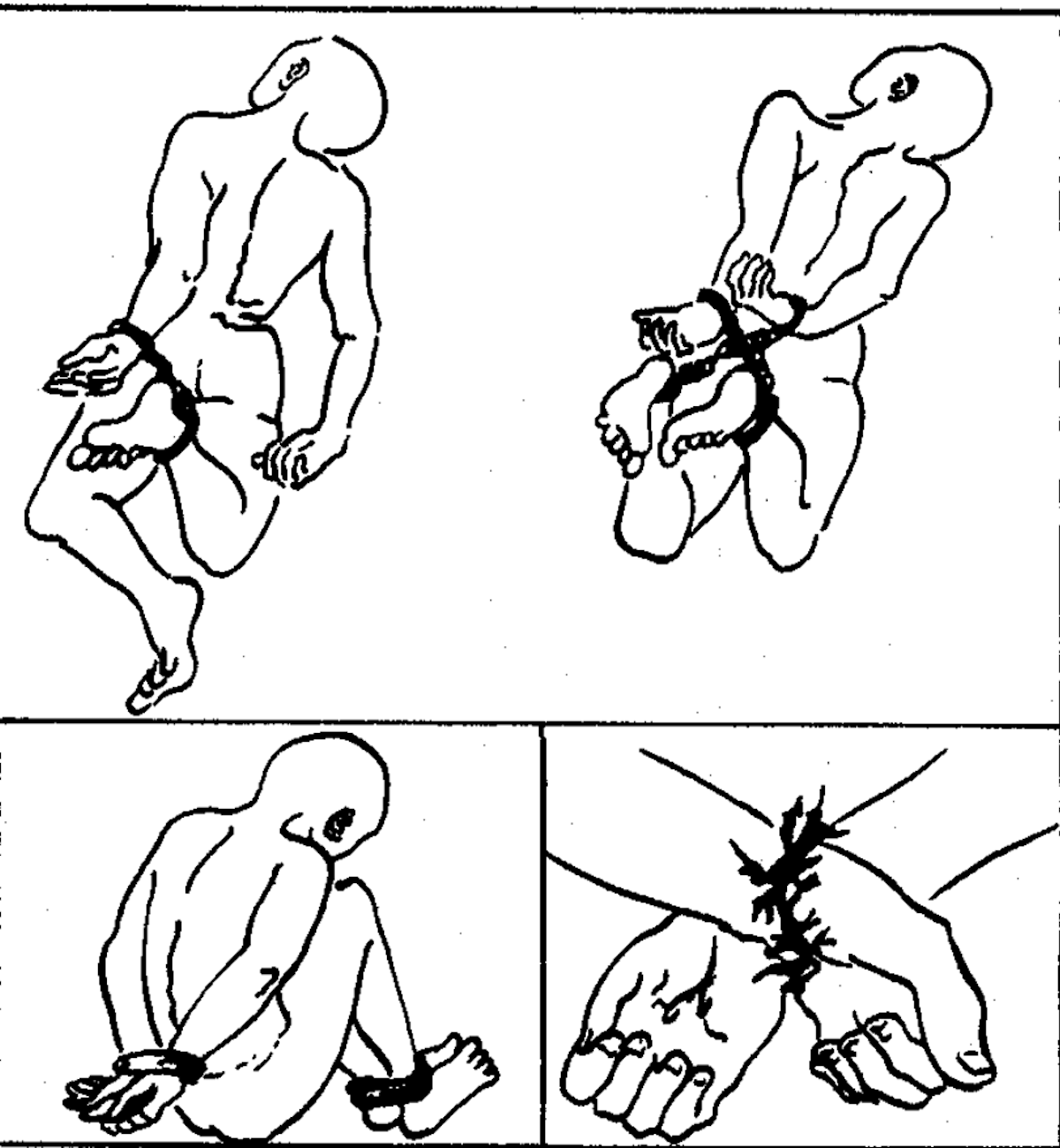

In addition, prison guards could punish prisoners in various ways, which sometimes also led to a prisoner’s death.

Nguyen Van Trong also told of a case where the re-education camp guards forced a prisoner (who intended to escape) to be confined in a box placed underground for three weeks. Every day, they dropped a handful of rice for him to eat. He was then hung high by his arms and beaten to death. His body was taken out of the box, and prison officials continued to beat his corpse to terrify other prisoners. [38]

Col. Nguyen Tho Lap said the guards once discovered a prisoner approaching the camp fence at night. This prisoner was then detained and locked in a container. Two weeks later, the guards pulled out his body and placed him in a coffin. [39]

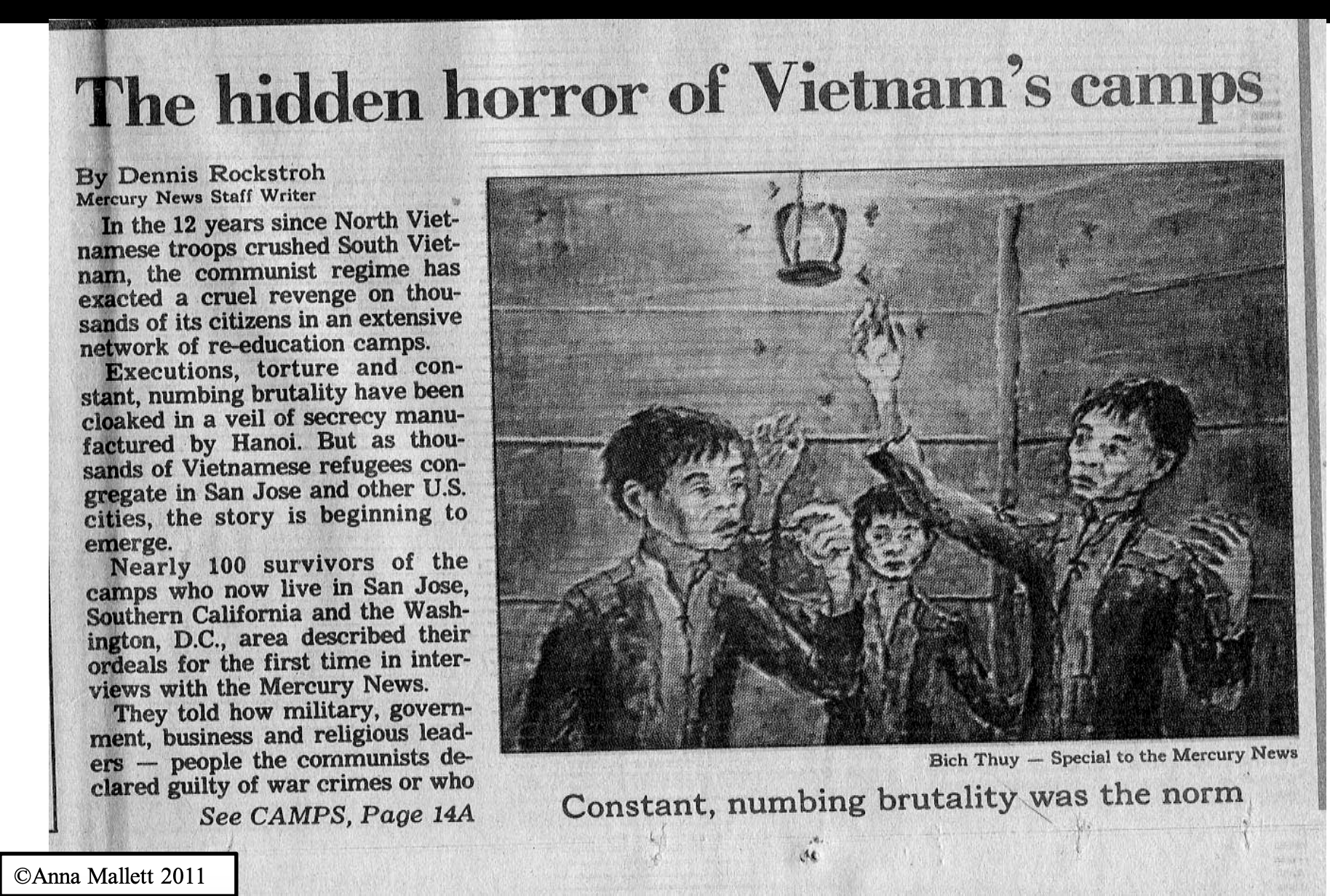

In the 1980s, the brutality of the re-education camps in Vietnam finally became known internationally through the accounts of former re-education prisoners who escaped the country by boat. Vietnam faced harsh international backlash for its inhumanity in these camps.

In 1987, the international media reported a statement by Justice Minister Phan Hien, confirming that the punishment of re-education camp prisoners was a reality. Phan Hien’s statement stated that Vietnam was treating re-education prisoners benevolently and humanistically. However, those prisoners who violated the camp’s regulations or tried to escape must be punished. [40]

In response to international accusations that prisoners were starving, in 1987, Hanoi's spokesperson for the Vietnamese Mission to the United Nations in New York responded: "We are a poor country. These people [re-education camp prisoners] were used to living in luxury. They received billions of dollars from the Americans. We have had trouble feeding our people, and we have had trouble feeding these prisoners, too.” [41]

However, the punishment was not confined to prisoners who were still in the reeducation camps. When prisoners were released and allowed to return to their families, the government punished them.

From 1977 to 1978, the Vietnamese government began to release a number of low-ranking former soldiers of the Republic of Vietnam from the re-education camps so that they could return to their families. However, these people remained under strict supervision.

A captain released at the end of 1978 said he could not go more than 5 km from his home and could not do anything to earn a living. [42]

Another person said he had to report to the local police weekly and that the reporting became monthly after a bit. Whatever he and his relatives did was monitored by the local police. [43]

A former ARVN soldier, after spending seven years in a re-education camp, said he could not find any job other than driving a pedicab (xích lô). [44]

After being released, the government required many prisoners to relocate with their families to new economic zones outside of Saigon or to work collectively for many months in rural areas.

A former prisoner named Nguyen Manh Hung, released in 1978, said that he had promised his re-education prison guards that he would work in agriculture if he was released and allowed to return to his hometown. [45]

A U.S. report in 1984 mentioned that the Vietnamese government refused to issue documents to former re-education prisoners so that they could find jobs and housing. Nor did it issue identity cards for them to travel within the country. And furthermore, it refused to let them participate in the U.N. Orderly Departure Program. At the time, Vietnamese people were not allowed to go to the United States as former officers and soldiers of the Republic of Vietnam, but could only depart under the family reunification program if they had relatives in America). [46]

In 1986, The Leader-Post newspaper reported that a number of Vietnamese boat people who had arrived in refugee camps were young men and women. This group of young refugees had parents who worked for the government or served in the RVN military. Because of that, they did not have the opportunity to study or advance in their careers in Vietnam. [47]

A colonel who was an internee in a re-education camp for 14 years said that none of his nine children were allowed to work for the new government. His children had to work as pedicab drivers and bricklayers. [48]

At this time, Vietnamese people believed that the government was applying a three-generation discrimination policy for those who were soldiers and employees of the Saigon government. Therefore, they had no choice but to cross the border and escape by boat.

In the late 1980s, more than 10 years after the war ended, the Vietnamese government knew it could not keep prisoners in re-education camps forever.

At this time, Vietnam wanted to improve its image internationally, especially in its attempt to normalize its relationship with Washington. The issue of re-education prisoners was of great concern to the United States.

In September 1987, Vietnam pardoned 480 prisoners in re-education camps who were soldiers and civil servants of the old regime. Among these were two ministers, 18 senior government civil servants, nine generals, including General Nguyen Huu Co, and many other Republic of Vietnam military officers. However, there were still about 7,000 people detained in re-education camps that year. [49]

During the Lunar New Year holiday of 1988, the government grant amnesty to another 1,014 prisoners. Ten generals were released, including Tran Van Cam and Nguyen Vinh Nghi. [50]

In July 1988, the United States reached an agreement with Vietnam to bring 11,000 former re-education camp prisoners and more than 40,000 of their relatives out of Vietnam. [51]

The agreement helped the United States open a special resettlement program for re-education camp prisoners, also known as the "Humanitarian Operation (H.O.)" program. Previously, South Vietnam’s military veterans could also come to the United States for family reunification under the Orderly Departure Program (O.D.P.).

In 1989, the United States accepted any former prisoner who had been in a re-education camp for more than three years. [52] At this time, Vietnam still held about 100 prisoners. [53]

In 1990, the number of former South Vietnamese military officers and soldiers coming to the United States was estimated to be about 1,000 people per month. [54]

However, Vietnam requested the United Statesto to accept of up to 60,000 people. [55] Furthermore, the United States, at the same time, also had to process hundreds of thousands of dossiers of other Vietnamese people who had left under other categories, such as mixed-race children (Amerasians) and those coming for family reunification. [56]

Therefore, the speed at which the United States processed the resettlement documents of former prisoners was quite slow. Combined with the fear of being arrested again and being sent back to re-education camps, some prisoners chose to escape as boat people.

In May 1992, Le Van Bang, Vietnamese ambassador to the United States., commented that on the commemoration of April 30 of that year, Vietnam would release all remaining prisoners, which he claimed was a humanitarian gesture. [57]

In the mid-1990s, the United States continued to accept about 10,000 former re-education camp prisoners and their families each year. [58] Statistics show that in 1997, 468,500 Vietnamese people came to America as former re-education camp prisoners with their relatives. [59]

At that time, only 145 families were waiting for their interviews to resettle in the United States. Since then, the issue of re-education camps has gradually faded from newspaper coverage.

Nevertheless, Vietnam has never disclosed the number of individuals who perished in re-education camps. For the surviving former internees, memories of their time in these camps continue to be a haunting and obsessive presence throughout their lives. This unresolved history also leaves the next generation grappling with a poignant question: Why were their parents and grandparents subjected to such harrowing conditions?

Vietnam's independent news and analyses, right in your inbox.