What The Economist Really Revealed About Việt Nam

On May 22, The Economist published a bombshell article about Việt Nam’s top leader, General Secretary Tô Lâm, highlighting

Since the beginning of its history, the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP) has been portraying itself as a group of nationalists who liberated the country from foreign intervention. History textbooks, propaganda, and official VCP narratives were all dedicated to showing that the VCP is the true heir of Vietnam and that the path to socialism is the destined path of the country.

However, this nationalistic sentiment contrasts with the Party’s cherished Marxist-Leninist Communist ideology, which states that nationalism is a bourgeoise illusion[1] that distracts people from their struggle with the bourgeoisie and that only international class struggle matters.[2] Such an ideological paradox is even more puzzling as we examine the regime’s responses to the rise of contemporary anti-China nationalism in Vietnam.

Anti-China nationalist sentiments have been rampant in Vietnam since the late 2000s, as expressed through various protests, demonstrations, and online debates. These sentiments are popular among the anti-communist Vietnamese diaspora and among the people residing in the country who were enraged by China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea. Since 1947, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has established an eleven-dash line map (now the nine-dash line map), claiming various islands in the South China Sea, including the Paracel and Spratly islands – or in Vietnamese, the Hoang Sa and Truong Sa islands.[3]

For years, the CCP has not relinquished claims to what Vietnamese nationalists insist are Vietnam’s rightful territories. Ten years ago, in 2011, anti-China nationalism manifested itself in the form of demonstrations, when hundreds of Vietnamese people protested in front of the Chinese Embassy in Hanoi, demanding China stay out of the Paracel and Spratly islands.[4] However, these demonstrations were met with repression from the Vietnamese regime.[5]

On the one hand, the VCP faces widespread nationalist criticism from its citizens for depending on China. Such criticism presented a considerable threat for the regime’s long-established narrative as nationalists fighting foreign influence and as the only legitimate ruler of the country.

On the other hand, the VCP faces the CCP, whom they have relied on for ideological and policy guidance and economic and military aid during wartime. Distancing itself from the CCP would also betray Marxism-Leninism’s internationalist agenda.

In a research essay, political scientist Tuong Vu, professor at the University of Oregon, examines contemporary anti-China nationalism in Vietnam as well as the Vietnamese regime’s responses. In a research essay titled “The Party v. the People: Anti-China Nationalism in Contemporary Vietnam,” Professor Vu argues that the suppression of anti-China nationalism is in line with the VCP’s international communist ideology, despite the Party’s nationalist image.[6] This article focuses on explaining the VCP’s repressive actions by analyzing their understanding of communism and nationalism.

Tuong Vu is a professor and head of the Political Science department at the University of Oregon. His research focuses on state formation, nationalism, ideology, and revolutions in East Asia.

In order to understand why the VCP suppressed anti-China nationalism, we must first grasp the VCP’s understanding of nationalism itself. The VCP sees nationalism as communism, with an emphasis on communist internationalism that promotes solidarity among socialist states. This suggests that opposition to other socialist states – in this case, China – is not seen as nationalism.

Since its foundation during the French colonial period, the VCP has always pursued two goals simultaneously: achieving national independence, which concerned the French and other foreign intervention, and carrying out a socialist revolution in the country.

To achieve the former goal, the VCP has always portrayed itself as a nationalist faction. Even foreign scholars seem to push the popular narrative that VCP leaders like Ho Chi Minh were nationalists first and communists second and that communism was a mere tool for them to achieve national liberation.[7]

However, Tuong Vu disagrees with this narrative. He thinks that the VCP has always been devoted to communism, even when it pushes a nationalist propaganda. But how did the VCP reconcile being both nationalist and communist, since being the latter means condemning nationalism?

Tuong Vu offers a simple explanation. Communism has always been portrayed as the best path to achieve liberation as well as decolonization for Vietnam. It was not just regarded as a tool for nationalism, but instead both the means to achieve independence, as well as the end goal for building the nation. Therefore, anyone who does not support communism is deemed unpatriotic.

In other words, the VCP ties nationalism or patriotism with being loyal to its own causes. This was demonstrated by the former Prime Minister Pham Van Dong, who declared that “to be patriotic is to build socialism.”[8]

Communist leaders such as Ho Chi Minh and Le Duan have also consistently tried to incorporate nationalism into communism by demonstrating that communist internationalism, solidarity with workers and communists worldwide, is a part of Vietnamese nationalism. [9]

As Le Hong Phong and Ha Huy Tap, leaders of the Indochinese Communist Party, the predecessor of the VCP, explained in 1936: “We believe in internationalism, not nationalism, but…we should raise the spirit for national liberation while tying it to the interests of the working masses….”

So nationalism for the VCP is communism. The VCP’s nationalism is particularly tied to its belief in internationalism, which says that “socialist brothers” around the world should find solidarity together instead of fighting each other like capitalist countries.

Additionally, the VCP also distinguished communist-nationalist movements from the other nationalist movements that it deemed to be bourgeoisie, and as a result it prioritized the former.

For instance, the VCP endorsed China in the Sino-Indian border war in 1962, even though the Communist Party of India criticized China and supported the Indian government. The VCP saw the Communist Party of India as having “sunken deeply in the bourgeois nationalist mud by colluding with the Indian bourgeoisie to slander a brother communist party,” based on archival materials collected by Tuong Vu.

This is important because it marks the VCP’s tactic when confronted with a reality that does not fit into their view of communist internationalism.

The VCP’s actions of justifying reality by creating more theoretical arguments to support its action do not stop there, as its idea of nationalism based on communist internationalism was further challenged by the fact of infighting among communist states the Sino-Soviet split (1956-1966), in which China was at odds with the Soviet Union, and the Sino-Vietnamese border war in 1979, in which China assaulted Vietnam’s border after Vietnam attacked the China-backed Khmer Rouge regime.

Accommodating reality, the VCP shifted its own narrative on nationalism by focusing more on domestic communist propaganda. Nevertheless, this new narrative still links Vietnamese nationalism with communism and internationalism. This shows that even when Vietnam was threatened by China, the VCP was still following communist internationalism instead of endorsing a more nationalist approach.

This is evident in the way the VCP has never acknowledged the Sino-Vietnamese border war as a war between socialist brothers. Just as when it justified endorsing China over India in 1962, the VCP argues that the border war was not about communist infighting. The conflict, argues the VCP, was “a fierce struggle between national independence and socialism on the one hand and aggression, expansionism, and chauvinism on the other, between Marxism-Leninism on the one hand and Maoism on the other.” This denial of reality demonstrates a deeply rooted ideological loyalty to Marxism-Leninism.

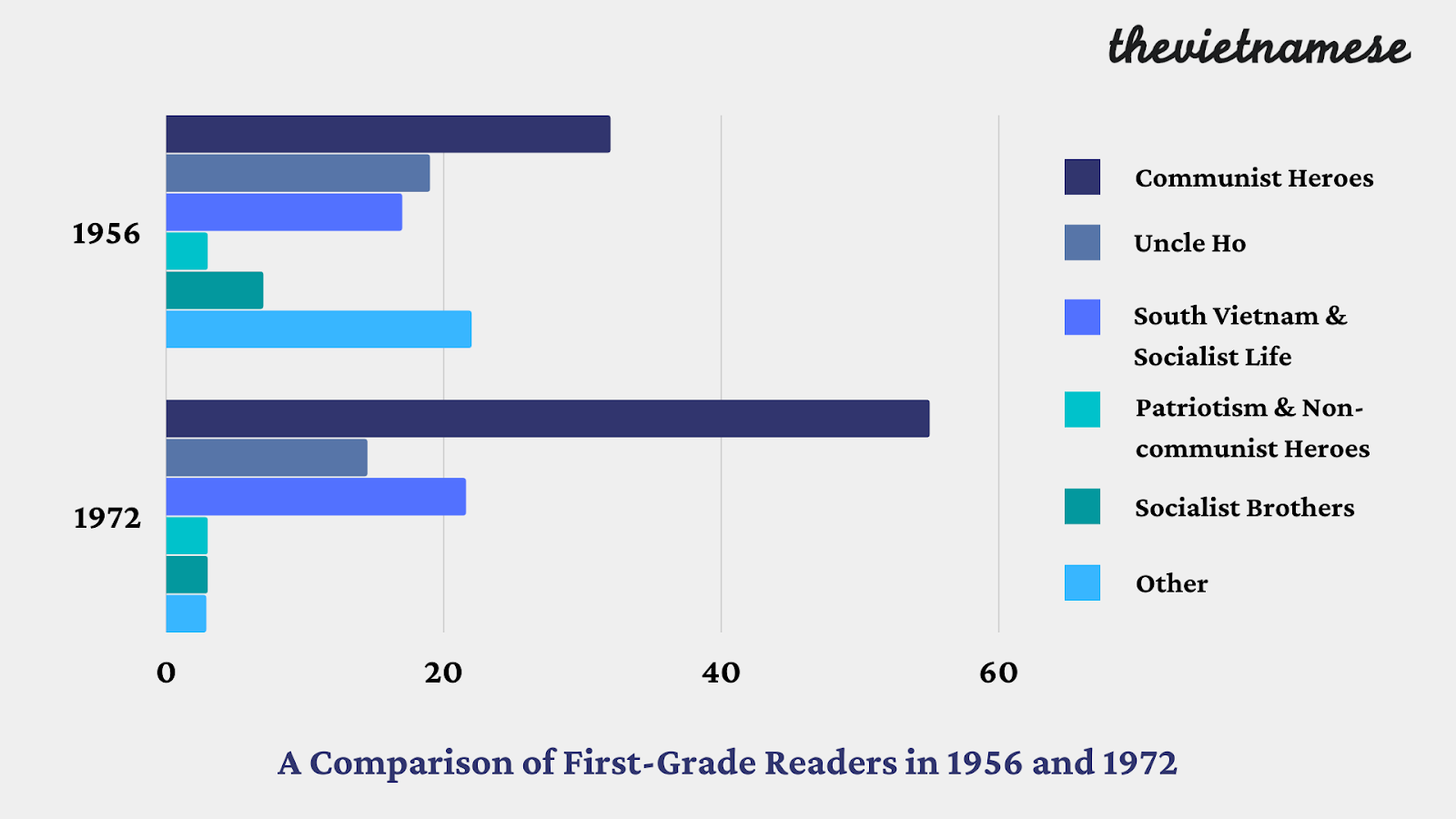

In order to demonstrate how the VCP justified the Sino-Soviet split, Tuong Vu looked into the VCP’s construction of historical narratives through the most basic and widespread document: the First-Grade Reader (Tập Đọc Lớp Một), a textbook used to teach first-grade children to read. He compared the two editions of the textbook, the one published in 1956, which was before the Sino-Soviet split, with the one published in 1972, after the split.

Firstly, there was significantly more content on communist heroes and less content on other socialist countries in the latter edition. This was due to the prolonged war, which produced more “heroes”, and because the VCP seemed to focus more on glorifying internal communist mobilization after the Sino-Soviet split. Additionally, these communist heroes were portrayed as both nationalist and communist – their struggle was seen as both contributing to the country and the international construction of communism worldwide.

Secondly, the content on non-communist heroes and patriotism not linked to the VCP was consistently low in both editions, and particularly low compared to the amount of content on communist heroes.

This reaffirms that the VCP constructed nationalism not based on ethnic lines but rather on political ideology, which suggests that the Party is more likely to align with a foreign communist force than to align with Vietnamese nationalists who reject communism.

The VCP’s loyalty to communist internationalism as a part of its nationalism was fiercely challenged by the wave of anti-China nationalism in 21st Century Vietnam due to China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea.

Anti-China opposition in Vietnam is expressed through two main channels: protests and debates on alternative understandings of nationalism. Both of these channels pose significant threats to the VCP’s legitimacy.

Ten years ago, in 2011, massive anti-China protests broke out on the streets of Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, especially in the areas where the Chinese embassy and consulate were located, to protest China’s harassment of Vietnamese fishermen in the Spratly and Paracel islands.[10]

The protests did not happen just once, but rather multiple times throughout the summer of 2011 for almost three consecutive months. While these protests were significant, they were not the first. In 2008, many democracy activists and bloggers were also arrested or detained for protesting China’s claims in the South China Sea.[11]

Alongside the protests, many Vietnamese intellectuals started to question the legitimacy of the VCP as Vietnam’s only ruling party and its construction of communist nationalism. Many retired, high-ranking government officials joined in these debates.

For example, Tong Van Cong, former editor of the state-controlled newspaper Lao Dong, argued that the true wish of the late Ho Chi Minh was to establish democracy for Vietnam rather than achieving socialism at any cost, thus questioning the Party’s nationalism based on ideology, as well as its refusal to institutionalize democracy.[12]

The late Le Hieu Dang, former vice-president of the Vietnam Fatherland Front in Ho Chi Minh City, a strong umbrella association of communist organizations, also expressed his dissatisfaction with the VCP’s ideological relationship with China.[13]

While he joined the communist movement during wartime due to his love for his country, Dang argued that the VCP had failed to pay back the debt it owed the Vietnamese people after they fought for and supported the Party. This debt was piled on to the Party’s failed policies based on China’s policy advice, resulting in misery for many Vietnamese people. In contrast, he argued that the VCP owes China nothing. This argument contradicted the Party’s narrative that the country owed China for its generous support for Vietnam in wartime.

Joshua Kurlantzick, senior fellow on Southeast Asia for the Council on Foreign Relations, believes that the protests did not merely demonstrate anti-China sentiments, but also showed the protesters’ frustration with the government’s repressive actions towards dissents over the years, and the government’s failure to deliver democracy.[14]

This further explains why the VCP oppressed anti-China protests and saw the protesters as a threat. These protests were seen as opposing a foreign regime and opposing the VCP, the only “legitimate” ruling body in Vietnam.

Currently, the VCP’s policies towards China are once again being challenged, this time by the COVID-19 pandemic, especially when it comes to vaccines. After resisting China’s vaccine diplomacy for a while, the government has recently approved the Chinese Sinopharm vaccine, and it was met with opposition and hesitation from a lot of Vietnamese people.[15] The VCP’s late approval was either because of its distrust of China’s vaccine diplomacy, or because the public opinion in Vietnam has been strongly anti-China.

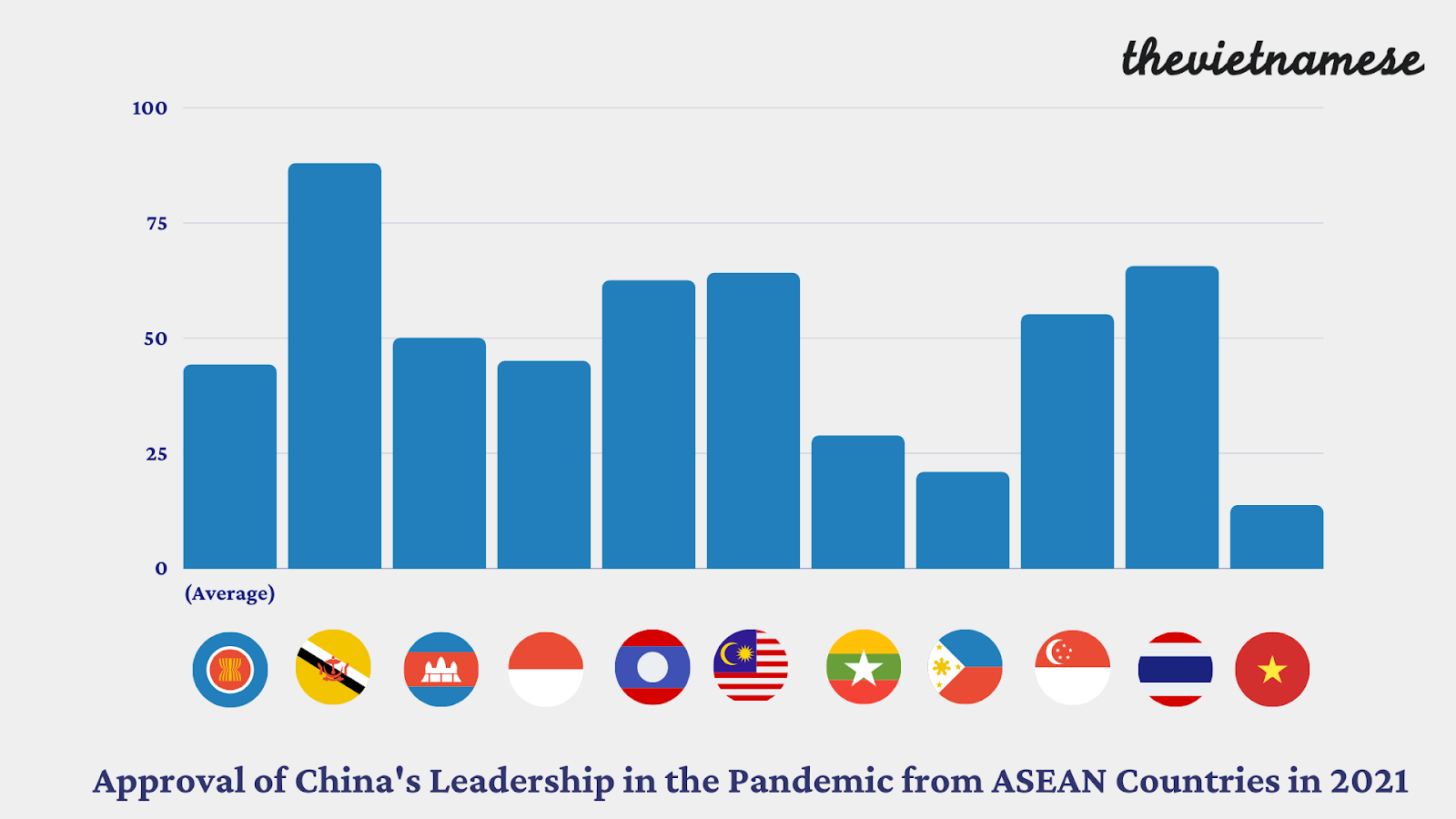

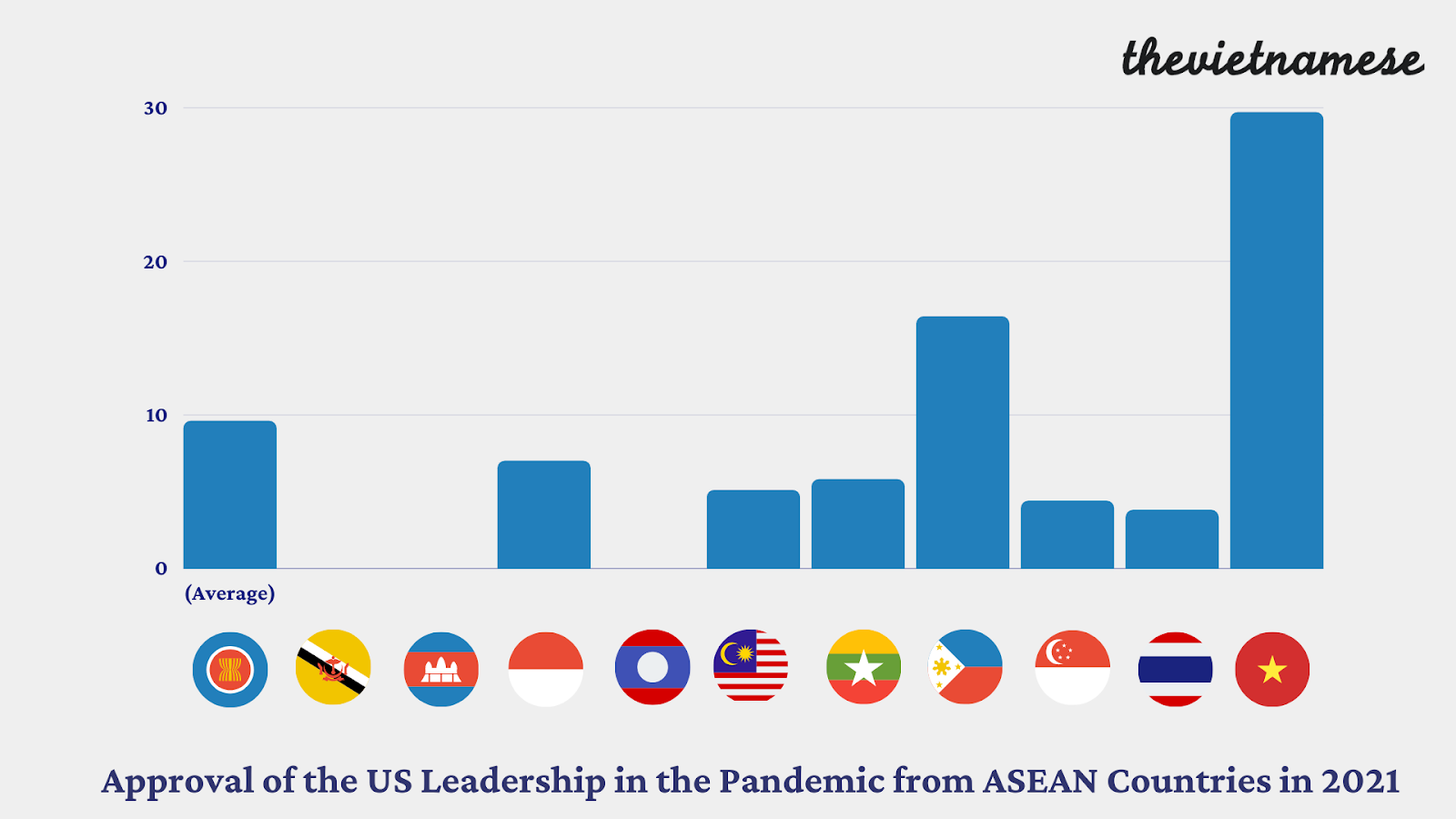

In a survey conducted by the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in 2021, individuals from Vietnam are the most disapproving of China’s leadership in the pandemic among 10 ASEAN countries, significantly more disapproving than others.[16] In contrast, Vietnam is the most approving of US leadership in the pandemic among these countries, much more so than the average ASEAN country.

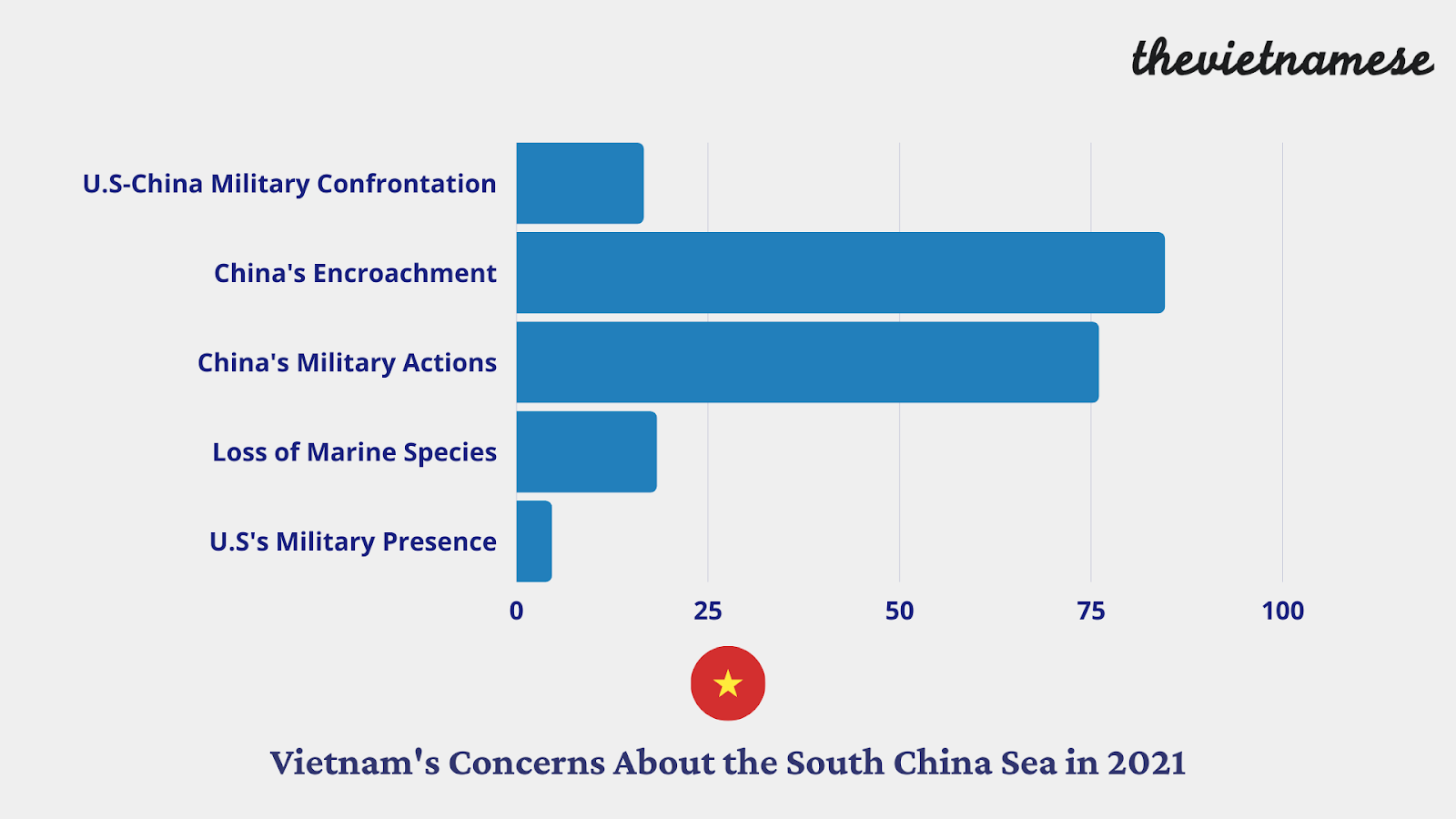

When it comes to the South China Sea, Vietnam also shows the most concern with China’s actions – its encroachment and military activities – rather than the US military presence or an escalation of the situation between the US and China.

Once again, this is a rather ironic situation, as the ideological doctrine of the VCP has been consistently promoting solidarity with other socialist countries while condemning capitalist and imperialist states such as the United States.

This shows that the VCP’s communist internationalism is not working. Arguably, it is even backfiring because Vietnamese public opinion is shifting towards supporting the United States – a capitalist and imperialist superpower according to Vietnam’s propaganda – instead of supporting China – a socialist brother.

On the surface, increasing anti-China sentiments among the Vietnamese people seem to be in the VCP’s favor, as it hopes to reclaim the Paracel and Spratly islands.

However, this anti-China nationalism also presents a great threat to the VCP establishment that is loyal to communist ideology which promotes solidarity among socialist states. It also presents a deeper ideological threat to the VCP, as Vietnamese nationalists begin to question the VCP’s version of nationalism that correlates being a patriot to being a communist.

The anti-China protests and data on popular opinions suggest that despite the VCP’s efforts, the Vietnamese people are feeling more and more detached from the socialist solidarity with China that the VCP has consistently promoted.

If the VCP continues to refuse to change its ideological approach to China, and if it continues to repress anti-China nationalism, it runs a grave risk of getting its own Marxist-Leninist legitimacy further questioned and challenged.

[1] Crawford, T. (1923, August 15). Bourgeois Nationalism. Marxists Internet Archive. https://www.marxists.org/archive/roy/1923/08/15a.htm

[2] McLellan, D. T. (1998, July 20). Marxism – Class Struggle. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Marxism/Class-struggle

[3] Xu, B. (2020, July 15). China’s Maritime Disputes. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/timeline/chinas-maritime-disputes

[4] Ide, B. B., & Orendain, B. S. (2011, June 4). Hundreds of Vietnamese Stage Anti-China Protest. Voice of America. https://www.voanews.com/east-asia/hundreds-vietnamese-stage-anti-china-protest

[5] Vietnam breaks up anti-China protests. (2012, December 9). The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/dec/09/vietnam-breaks-up-anti-china-protests

[6] Vu, T. (2014). The Party v. the People: Anti-China Nationalism in Contemporary Vietnam. Journal of Vietnamese Studies, 9(4), 33–66. https://doi.org/10.1525/vs.2014.9.4.33

[7] Buttinger, J. (1977). The Journal of Developing Areas, 11(3), 423-425. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4190492

[8] Le, H. N. (2016, February 29). Phạm Văn Đồng – Nhà Chính trị, Nhà Văn hóa lớn của Đảng và Dân tộc. Báo Nhân Dân. https://nhandan.vn/tin-tuc-su-kien/pham-van-dong-nha-chinh-tri-nha-van-hoa-lon-cua-dang-va-dan-toc-256438

[9] Nguyen, C. T. (2018, July 31). Tư tưởng Hồ Chí Minh Về Tinh Thần Yêu Nước. Tạp Chí Quốc Phòng Toàn Dân. http://m.tapchiqptd.vn/vi/theo-guong-bac/tu-tuong-ho-chi-minh-ve-tinh-than-yeu-nuoc-12158.html

[10] Vandenbrink, R., & Nguyen, A. (2011, June 5). Anti-China Protests in Vietnam. Radio Free Asia. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/vietnam/protests-06052011165059.html

[11] Human Rights Watch. (2020, October 28). Vietnam: New Round of Arrests Target Democracy Activists. https://www.hrw.org/news/2008/09/12/vietnam-new-round-arrests-target-democracy-activists

[12] Tong, V. C. (n.d.). Nhân Ngày sinh lần thứ 120 Chủ tịch Hồ Chí Minh: Vì Sao Hồ Chí Minh Đặt Dân Chủ Trước Giàu Mạnh? Bauxite Vietnam. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://boxitvn.blogspot.com/2010/05/nhan-ngay-sinh-lan-thu-120-chu-tich-ho_19.html

[13] Le, H. D. (n.d.). Suy Nghĩ Trong Những Ngày Nằm Bịnh. . .. Bauxite Vietnam. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://boxitvn.blogspot.com/2013/08/suy-nghi-trong-nhung-ngay-nam-binh.html

[14] Kurlantzick, J. (2014, May 16). Vietnam Protests: More Than Just Anti-China Sentiment. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/blog/vietnam-protests-more-just-anti-china-sentiment

[15] Nguyen, S. (2021, June 7). Vietnam Briefing: Busy With The Pandemic, But The Government Still Cracks Down On Free Speech. The Vietnamese Magazine. /2021/06/vietnam-briefing-busy-with-the-pandemic-but-the-government-still-cracks-down-on-free-speech/

[16] Seah, S., Hoang, T. H., Martinus, M., & Pham, T. P. T. (2021, February). The State of Southeast Asia: 2021 Survey Report. ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/state-of-southeast-asia-survey/the-state-of-southeast-asia-2021-survey-report/

Vietnam's independent news and analyses, right in your inbox.