A Teacher’s Reflection on Loyalty, Love, and the Story “Làng”

Đan Thanh wrote this article in Vietnamese, published in Luat Khoa Magazine on July 3, 2025. First and foremost, I

Religious activists in Vietnam are paying a heavy price, sometimes putting their lives on the line.

The former head of Thien An Abbey has been prevented from returning home after traveling to Europe to treat a suspected poisoning. Check out [The Government’s Reach] to find out how the government punishes religious activists. For the first time, figures for the number of Falun Gong practitioners in Vietnam are available; see them in [Religion 360*]. In [On This Day], a reminder of how the government installs surveillance cameras in many temples, and how the assault of six Hoa Hao Buddhist practitioners last year remains uninvestigated.

If you have any suggestions or would like to join us in writing reports, please email us at: tongiao@luatkhoa.org or editor@thevietnamese.org.

Religion Bulletin, October 2020:

The former head of Thien An Abbey – Father Anthony Nguyen Huyen Duc – is still waiting for the Vietnamese government to allow him to return home.

After a period of leading Thien An Abbey’s resistance against the government’s land reclamation attempts, Father Duc traveled to Europe to seek medical treatment after a suspected poisoning.

After his second medical treatment in Germany, he returned to Vietnam in September 2019, only to be told by police to return to Europe.

“Right when I returned to Hanoi, I was questioned by police. High-level officers asked that I return to Europe because they could not ensure my safety or my life if I stayed in Vietnam, that it would be extremely adverse for the Thien An community if I stayed at the abbey,” the organization BPSOS reported, quoting from a letter Father Duc sent to leaders of the Order of St. Benedict.

On October 16, 2020, the German diocese’s Committee for Justice and Peace sent a letter to Vietnam’s Justice Committee requesting they allow Father Duc to return to Vietnam.

The German committee requested that the Vietnamese government return the abbey’s confiscated property, cease its violence, protect and respect sacred religious objects, and uphold the right to freedom of religion.

BPSOS quoted Father Duc who stated that doctors in Europe also believe he had been poisoned.

Duc believes he was poisoned during the 2016 Lunar New Year at Thien An Abbey, when a person invited him to drink their tea and coffee.

“Right after the person left, I immediately felt sharp pains in my neck and head, aches down to my bones, my jaw became extremely sensitive and teeth came loose, I was unable to walk… a large (3 cm diameter) patch of my hair fell out…. Afterwards, I asked the sitting head Father Bruno for permission to travel to Europe,” BPSOS published, quoting from a letter written by Father Duc in August 2020.

Father Nguyen Huyen Duc was the head of Thien An Abbey from 2014 to 2017. The abbey is known for its heated and long-running land dispute with Thua Thien – Hue provincial authorities.

In past years, Thua Thien – Hue provincial authorities did not accept Father Duc’s presence at Thien An Abbey.

In December 2017, they requested leaders of the Order of St. Benedict to remove him as head of the abbey.

The authorities stated that Father Duc had allowed many unauthorized construction projects on disputed land, organized clergy appointments without permission, and obstructed government work.

After the government’s requesting letter, Father Duc took time off to travel to Europe for medical treatment. Leadership of the abbey was passed to another person.

In May 2019, as Father Duc was preparing to resume his position as head of Thien An Abbey, provincial authorities continued to insist that he should not take up the position.

In a May 2019 document, provincial authorities accused Father Duc of “distorting the situation, and inciting ethnic hatred and opposition against the Socialist Republic of Vietnam” while he was getting medical treatment overseas.

Religious activists like Father Duc have long endured many forms of harassment and suppression. Below are the systematic methods in which religious activists are suppressed, methods which are sometimes openly carried out by police, and at other times, by anonymous individuals.

In February 2018, many anonymous pro-state web pages published information alleging that Father Duc had entered a hotel with a woman.

According to the Catholic webpage Good News To The Poor, Father Duc’s stay at the hotel occurred in September 2017

Accordingly, Father Duc had arranged to meet with a group of overseas Vietnamese from Canada at the hotel in Ho Chi Minh City. This meeting was facilitated by a woman who was acquainted with both sides.

When Father Duc checked into his hotel room, approximately 100 plainclothes and uniformed police officers poured into the hotel in a prostitution raid. Father Duc was interrogated in a room. Police ultimately forced the woman to sit next to Father Duc and took a picture of them together.

Rumors intended to smear individuals are regularly posted on anonymous pro-state websites and shared with the public. The source of these rumors is one big question mark.

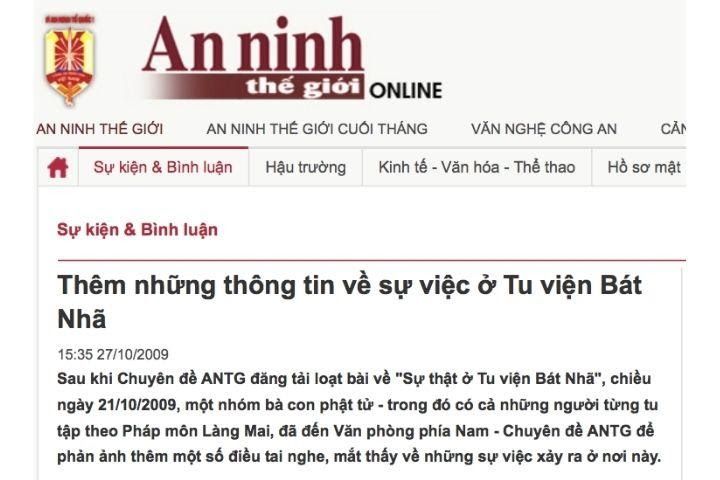

There are reasons to believe that Vietnamese police are directly involved. In 2008, after Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh’s Letter #31 spoke of religious freedom and politics in Vietnam, the first students of Hanh’s Plum Village met with difficulties.

In August 2008, Plum Village students were expelled from Bat Nha Monastery and continuously harassed in a variety of ways.

During the Bat Nha Monastery affair, the People’s Public Security Daily — the official mouthpiece for police — published an article citing a number of anonymous sources regarding the romantic relationship between Zen Master Nhat Hanh and Nun Chan Khong, as well as the dictatorial way in which Nun Chan Khong controlled Plum Village.

The article was published precisely when Plum Village was receiving public support in the Bat Nha Monastery affair.

According to the webpage Good News To The Poor, in September 2017, a car driving Father Duc’s delegation was purposefully rammed by a pick-up truck after they visited Father Dang Huu Nam – who advocated parishioners sue the company Formosa for polluting the central Vietnamese coast. Father Nam stated that this same pick-up truck had purposefully rammed his vehicle many times.

In October 2019, six independent Hoa Hao Buddhists were ambushed and attacked by a group of people on the road to An Hoa Temple. These six practitioners were planning to prevent a roof re-tiling at the temple but were attacked before arriving. A practitioner threatened to cut his own throat and set himself on fire as they were being attacked by unidentified individuals.

The individuals who assault religious activists are often unidentified plainclothes people, and police normally do not pursue any kind of investigation after such incidents are reported.

In December 2015, Father Dang Huu Nam stated with Good News To The Poor that his vehicle was blocked by a group of 20 individuals, who pressured him to get out of the car and then proceeded to surround him and beat him.

“As the crowd of thugs beat me, the police chief of An Hoa Commune stood by on the side of the road and did nothing,” Father Nam told Good News To The Poor.

In June 2018, according to a Cali Today article, Mr. Hua Phi, an independent Cao Dai dignitary in Lam Dong, was beaten and his beard shaved. He stated that an individual identifying himself as police brought in dozens of others who entered his residence, “covering his head and beating” him repeatedly. The incident occurred just three days before he was to have a dialogue with the Australian Embassy regarding human rights issues.

Religious activists in Vietnam must be very careful in their conflicts with the authorities. Five out of six Hoa Hao Buddhists are in jail because of their clash with traffic police in April 2017.

These six practitioners, four of whom are from the same family, had opposed the traffic police confiscating the vehicles of those arriving at their house for a death anniversary. The tug-of-war between the two sides quickly turned into a case of disturbing public order and obstruction of officials.

In recent years, many social activists have been charged with disturbing public order in their conflicts with police.

Being prevented from returning home, as discussed at the beginning of the article with the case of Thien An Abbey’s clergyman, is rare. More frequently, religious activists are forbidden from traveling overseas; either the government confiscates their passports or they are not issued one at all.

In May 2020, Father Nguyen Van Toan was denied the issuance of a passport; he is a frequent and public government critic.

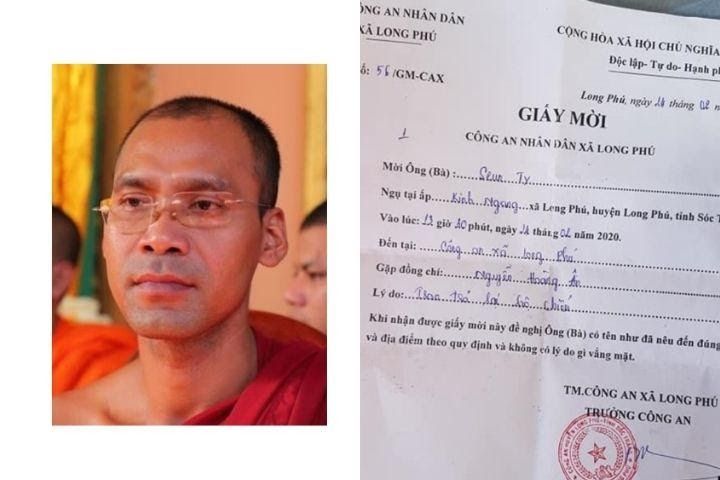

In February 2020, a Khmer monk named Seun Ty had his passport confiscated for two weeks. Police accused Mr. Seun Ty of violating the Cybersecurity Law.

In 2017 and 2019, authorities refused to allow Father Nguyen Dinh Thuc, head of Song Ngoc parish, to travel overseas.

The issue of travel bans on religious and social activists remains unresolved.

From the end of September to the beginning of October 2020, many state newspapers reported on the Gie-sua and Ba Co Do religions “raging in Dien Bien Province”.

The Voice of Vietnam (VOV) newspaper, a government mouthpiece, stated that in Dien Bien Province, 112 individuals returned to the Gie-sua religion after giving it up previously, while 294 others were currently following the Ba Co Do religion in Muong Nhe district.

Ms. Nguyen Thanh Huyen, vice-chair of the Public Relations Commission of the Dien Bien Provincial Committee stated that the government would push people who followed unrecognized faiths to give up their religion.

“A number of mountain villages have regulations and conventions, one of which states that anyone who participates in these religions [Gie-sua, Ba Co Do,…] will not receive [the benefits] of the regime and its policies”, Ms. Huyen stated to VOV.

Dien Bien provincial authorities reported that the Gie-sua and Ba Co Do religions operate differently from one another but shared the same goal of establishing an autonomous Mong state.

Muong Nhe district police chief Major Vu Van Hung added that authorities were using Protestant dignitaries to push people to give up these “heretic religions”.

“We’ve organized groups penetrating into households that follow these religions, courting group leaders and putting Protestant dignitaries in influential areas so that villagers will give up their religions. But the most economical method must be us using our resources to prevent unauthorized proselytizing online. Only then will we be effective,” Major Hung stated to VOV.

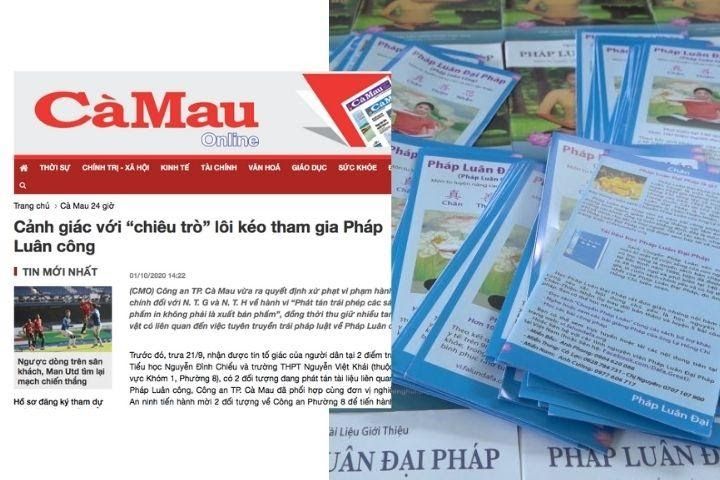

Vietnamese police continue to arrest practitioners of Falun Gong for spreading the religion.

The Ca Mau Daily reported that Ca Mau city police administratively punished two individuals on October 1, 2020 for distributing Falun Gong flyers without permission.

Two individuals with the initials N.T.G and N.T.H were arrested on September 21, 2020 after distributing approximately 65 flyers to parents and students in front of a school’s gate. Police confiscated from the two 177 flyers and 30 books on Falun Gong.

According to statistics from Luat Khoa, at least 66 Falun Gong practitioners have been arrested and administratively punished for spreading the religion since the beginning of 2020.

On October 22, 2020, Lam Dong Radio and Television broadcast a report stating that across the country, there were more than 8,300 Falun Gong practitioners. Lam Dong Province, in particular, has about 110 practitioners.

The news was particularly noteworthy, as up to this point, no one had an accurate count of Falun Gong practitioners in Vietnam. However, Lam Dong Radio and Television did not cite the source of this figure.

According to the report, Lam Dong Province had a number of party members, veterans, and teachers who practiced and spread Falun Gong. Among them was a deputy commune head.

The report stated that spreading the practice in Lam Dong Province was both illegal and harmed the people.

“Falun Gong is a religion that opposes science, convincing people that you can treat sickness without going to the hospital, it distracts people from finding livelihoods”, Lam Dong Radio’s reporters noted.

Provincial radio and television stated that those spreading Falun Gong in Lam Dong were being sent materials from other provinces.

On October 27, 2020, the Government Committee For Religious Affairs acknowledged that there were “Cao Dai organizations that operate independently and splinter in resistance” during a conference on religious management in Ben Tre Province.

However, the article described the conference without going into detail about the splintering or independent activities of the Cao Dai organizations.

As covered in Luat Khoa’s September 2020 Religion Bulletin, a number of independent Cao Dai temples are currently being pressured to merge with those temples being recognized by the government.

In recent years, the government has been helping state-recognized temples “take over” independent Cao Dai temples.

Although nearly all independent Cao Dai temples operate in a purely religious manner, the government views their independence as a security risk.

From the end of September through all of October 2020, the Government Committee For Religious Affairs organized conferences on “advocating the law to religious practitioners” in many locations: Hai Phong, Kon Tum, Gia Lai, Binh Dinh, and Bac Giang.

These conferences sought to familiarize Vietnam’s practitioners with the state’s strict religious management regulations. Furthermore, conferences in a number of provinces and cities also held exchanges on the teaching of two subjects, Vietnamese history and Vietnamese law, on the premises of religious organizations.

This is one way in which the state controls the people’s views over religions in Vietnam. Religious practitioners had to pay attention not just to legal regulations but also to the ways state bodies treat them.

Similar conferences are expected to take place across many other provinces and cities.

In October 2019, numerous monks raised objections to the government’s installation of a surveillance camera pointing directly at their temple’s front gates.

In Ba Ria – Vung Tau Province, Venerable Thich Vinh Phuoc stated that authorities had installed a camera in front of Phuoc Buu Temple before he had left for the United States to advocate for religious freedom.

“It’s been more than just Phuoc Buu Temple; for over a year, they’ve installed many cameras in Xuyen Moc District, as well as the whole Ba Ria – Vung Tau Province,” Venerable Vinh Phuoc told RFA.

The government also installed a surveillance camera at another temple in Ho Chi Minh City.

“Since 2000, there have been many difficulties because Thien Quang Temple refuses to abide by the Buddhist Church of Vietnam (BCV). Their [BCV’s] management has been unbearable, stifling”, Venerable Thich Thien Thuan told RFA regarding the reason for the surveillance cameras.

Also in Ho Chi Minh City is Venerable Thich Khong Tanh. He is temporarily residing at Giac Hoa Temple, which also had surveillance cameras installed.

“When I asked, they explained that the cameras were simply fulfilling a responsibility to monitor,” Venerable Khong Tanh told RFA. “These surveillance cameras deter democracy allies and friends from coming.”

In recent years, the government has installed surveillance cameras to monitor all kinds of activists.

These activists have stated that the government wants to monitor who comes and goes from their residences, as well as the activists’ own routines. During special occasions such as visits from foreign delegations, security forces will prevent activists from leaving their homes.

This October marks one year since the roof of Hoa Hao Buddhism’s An Hoa Temple was re-tiled. It also marks one year since six independent Hoa Hao Buddhists were beaten on the way to prevent this re-tiling.

The scuffle occurred on October 7, 2019, at the Thuan Giang ferry pier, about 1.7 kilometers away from An Hoa Temple.

The independent Hoa Hao Buddhists had all along opposed plans to re-tile the An Hoa Temple roof. However, the state-recognized Hoa Hao Buddhist Church moved forward with the plans anyway, ignoring the opposition.

The six independent Hoa Hao Buddhists involved include Vo Van Thanh Liem, Le Thanh Thuc, Nguyen Thanh Tung, Vo Thi Thu Ba, To Van Manh, and Le Thanh Truc.

Mr. Thanh Liem stated to RFA: “When we arrived at Thuan Giang ferry, there were about 40-50 people blocking us; they beat Mr. To Van Manh, Mr. Le Thanh Thuc, and Nguyen Thi My Trieu, and my granddaughter, Vo Thi Thu Ba, had her phone smashed. I saw that they were about to beat me so I poured gasoline on myself to threaten self-immolate, attempting to cut my own throat, and they ran off. They used long sticks and beat people so hard that the sticks were smashed to pieces”.

Today, more than one year after the scuffle, police still have not initiated an investigation into the matter.

Vietnam's independent news and analyses, right in your inbox.