In Death, All Debts Are Settled?

Đan Thanh wrote this article in Vietnamese, published in Luat Khoa Magazine on July 9, 2025. Đàm Vĩnh Hằng translated

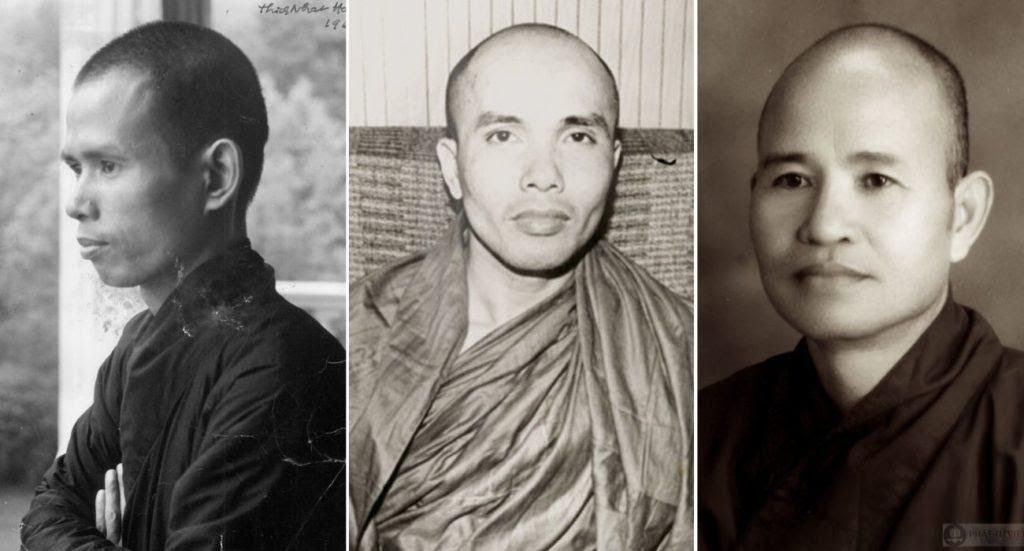

Long ago, there lived three monks: Thich Nhat Hanh, Thich Tri Quang, and Thich Quang Do. All three were well-versed in the Buddhist Dharma. Nhat Hanh spoke eloquently and wrote well. Tri Quang had talent for leadership and was trusted by the masses. Quang Dao was well-studied and excelled in foreign languages.

Long ago, there lived three monks.

When Ngo Dinh Diem’s regime cracked down on Buddhism, these three combined forces to fight back. Nhat Hanh campaigned overseas, calling for peace and religious freedom in Vietnam. Tri Quang led tens of thousands of monks and Buddhist adherents as they protested in Saigon. And Quang Do, the youngest of the trio, stood side-by-side with these Buddhists as they marched on the streets.

Long ago, there lived three monks.

When the communists arrived, the paths of these three diverged. Nhat Hanh became world-famous with his Plum Village Monastery. Tri Quang was imprisoned and refrained from speaking about politics again. Quang Do continued the struggle for religious freedom and human rights, ultimately serving the longest period of house arrest of any monk in Vietnam.

One day in October of 1997, in a theater in Berkeley, California, approximately 3,500 people, who paid US$20 a ticket to meet their most beloved monk, sat in silence.

A ringing bell echoed across the theater, and a monk’s voice loudly called out: “All rise!”. Zen Master Nhat Hanh, draped in a deep brown robe, lead 35 monks and nuns as they slowly spread out across the stage.

Many in the audience clasped their hands before their chests and directed their eyes towards the stage. Sitting on a high podium next to a large, bronze bell and an arrangement of giant sunflowers, Zen Master Nhat Hanh began expounding on mindfulness. “Learn how to stop running,” he advised his audience. “Many of us have been running all our lives.”

“Society is very individualistic, selfish, with people thinking about himself or herself alone. Each for himself, each for herself alone. But in fact even if you have the desire, the intention, to help others, it would still be difficult for you to do so, because when you are not in peace with yourself, it’s very difficult to relate to people in a peaceful way in order to help them,” he stated to reporter Don Lattin of the San Francisco Chronicle.

By that point, Zen Master Nhat Hanh had become internationally renowned for this talks on mindfulness and world peace. After 1975, he stopped speaking to the international media about human rights in Vietnam, even though Buddhism there was suffering through hardship.

At the same time, in a prison cell thousands of miles away from America, Venerable Quang Do was compiling a Buddhist dictionary. He was sentenced to five years in prison in 1995 for helping flood victims in the Mekong Delta. Ten years before that, he witnessed his mother pass away in hunger and poverty after the government exiled both to Thai Binh.

In 1997, Venerable Tri Quang grew accustomed to his comfortable life. He no longer spoke about politics or peaceful resistance.

After 1975, he was confined to a wheelchair to heal his feet, which had atrophied after government torture, according to a monk who was imprisoned with him at the time. From the 1980s onwards, the international media stopped mentioning him and the tragedies of Buddhism in the south.

Born during the tumult of French and Japanese fighting over control of the country, the three monks were all witness to the historical crises of that era.

One day in Diem Dien Village, Quang Binh Province, the mother of Tri Quang met two monks who left a deep impression on her, he relayed in his autobiography. Upon returning home, she told her husband that the family should have someone join the monastery, as the two monks had. Thus, on the eve of the lunar new year in 1938, Tri Quang shaved his head and entered the monastery at Pho Minh Pagoda; he was only 15 years old. The next year, he was transferred to Hue to study for another six years. When he was put in charge of the Quang Binh Province Buddhist Committee for National Salvation (seen as a part of the Viet Minh Front), he saw many of his classmates sacrifice their lives in the resistance war against the French.

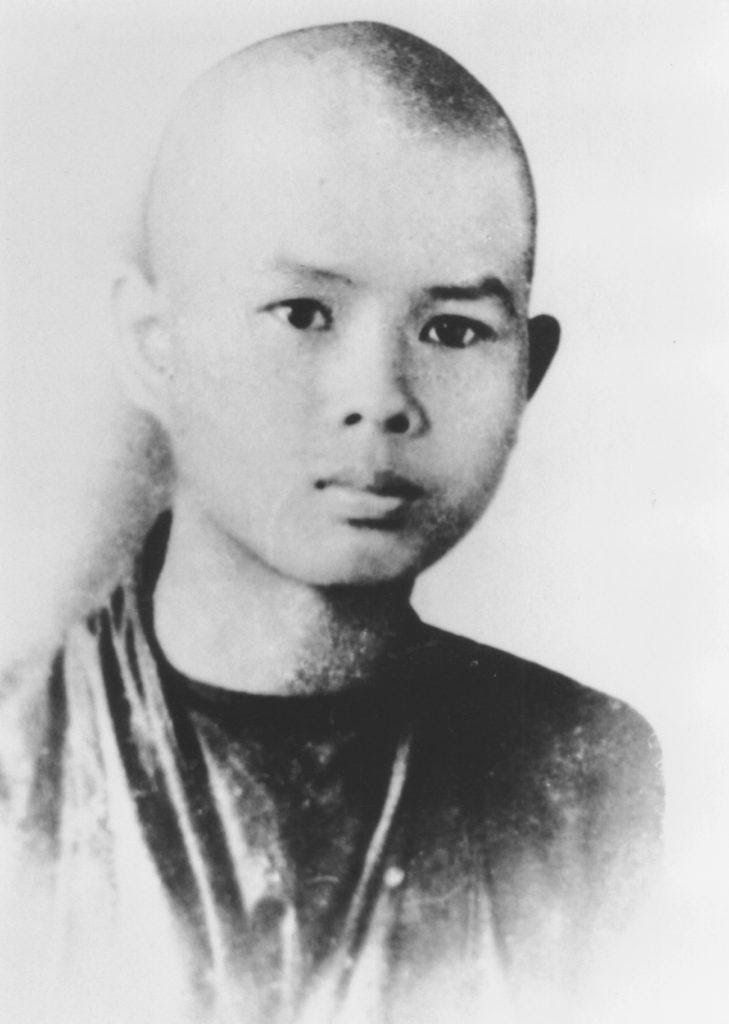

In Hue, Nhat Hanh grew up the son of a man who worked for Emperor Bao Dai’s government. Nhat Hanh stated the seed of the Great Buddha blossomed within him from when he was very young. Responding to reporter Don Lattin about his childhood, he stated that while he was studying at the village school, he and his friends would go door-to-door begging for bowls of rice to give to those dying of hunger. He relayed that the kids had to decide early on who would get to eat and who wouldn’t because there simply wasn’t enough rice to go around. In 1942, Zen Master Nhat Hanh left his family and entered the monastery at Tu Hieu Temple in Hue. He was only 16.

In the same year, a 15-year old teenager in Thai Binh traveled to Ha Dong province (today’s Hanoi) to enter the monastery at Thanh Lam Temple. He took on the Buddhist name Quang Do. He recalled, only three years after he left his family, he witnessed his master tied up and brought out to the village courtyard like a criminal, after the Viet Minh suspected him of being a traitor. His master was then denounced and executed by three bullet rounds. It was then the young 18-year old swore to himself that he would use Buddhism’s mercy, forgiveness, and non-violence to fight against fanatics and the unforgiving.

After the tragedy at Thanh Lam Temple, Thich Quang Do went to study in Hanoi. During this time, Tri Quang and Nhat Hanh likely met one another in Hue.

At the time, the Bao Quoc Buddhist Institute had just been established in Hue in 1947. A year later, Tri Quang became a teacher there, and Nhat Hanh a student.

In 1950, Tri Quang went to Saigon for the first time, concurrent with Nhat Hanh. In Saigon, Tri Quang, along with some other monks, unified three Buddhist institutes into one, locating it at An Quang Temple. Nhat Hanh began teaching here.

Both Nhat Hanh and Tri Quang had a common desire to unify Buddhism and develop it into a national religion [1]. Both pursued this desire through journalism.

After the Geneva Accords were signed in 1954 and the country was temporarily divided in two, Tri Quang became the editor-in-chief of the Vien Am paper. A year later, Nhat Hanh was made editor-in-chief of Vietnamese Buddhism, but after two years, he was forced to suspend the paper after pushing for Buddhist unification too vociferously.

During this time period, both individuals suffered enormous mental anguish. Nhat Hanh was completely “defanged” in his struggle and afterward temporarily withdrew from the limelight, retreating to a solitary location with allies in Lam Dong. Tri Quang, haunted by images of his mother being publicly denounced in 1956, wandered to Nha Trang before returning to Hue in 1960. Buddhism’s suppression (by Ngo Dinh Diem’s government) would add an extra layer of pressure on top of his mother’s tragedy.

In 1958, Quang Do returned to Saigon after studying abroad in Sri Lanka and India. Under Ngo Dinh Diem’s religiously discriminatory regime, and the conflict brewing between the Nationalists and the Communists hanging over their heads, young Nhat Hanh and Quang Do were not able to accomplish much in the way of big tasks. But it seems all three were able to sense impending disaster for Buddhism in the south.

In his book Intention’s Road Home, Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh explained that in 1961, when he and his friends’ place of residence was raided, he had to retreat to Saigon for safety. During this difficult time period, he traveled to the United States, where he conducted research on Buddhism at Princeton University and then taught at Columbia University.

On the night of May 8, 1963, as Venerable Tri Quang, head of central Vietnam’s Buddhist Association, stepped into Hue’s radio station together with the provincial leader to resolve ongoing protests as gunfire rang out among the Buddhist crowds surrounding the station. That night, Hue Radio did not broadcast as promised the program celebrating Vesak, recorded earlier that morning. Compounding popular anger was the fact that the government had prevented the flying of Buddhist flags. The crowds did not disperse until two in the morning. That night, many were seriously injured, resulting in eight deaths.

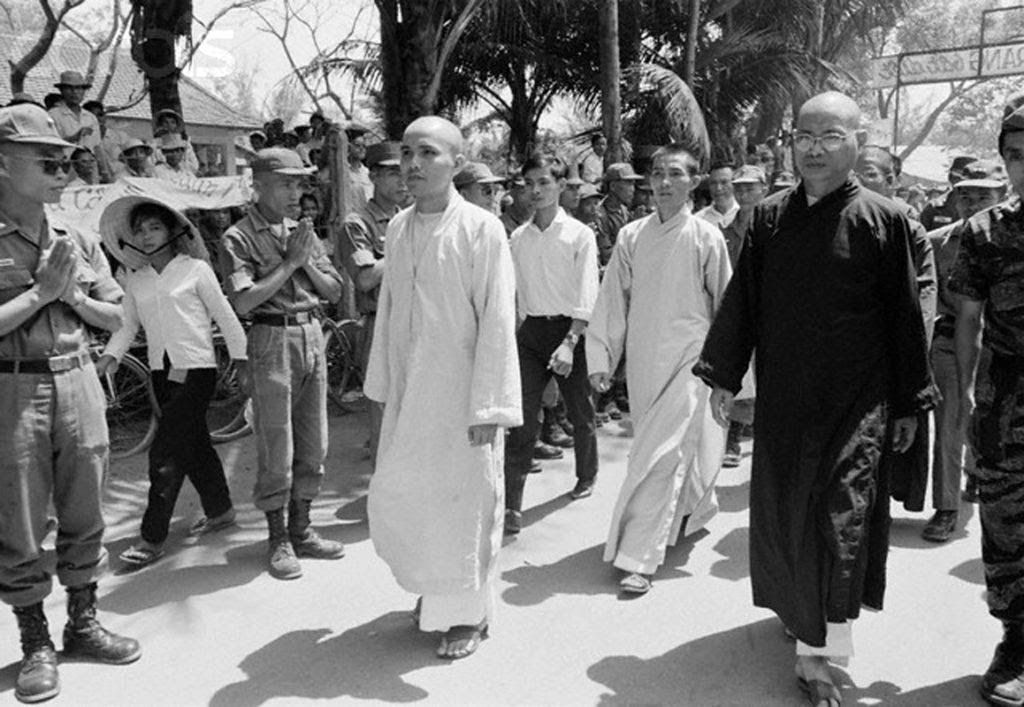

In the gloom of the next morning, as Venerable Tri Quang was resting, roiling crowds of young people began filling the streets, holding Buddhist flags. That same day, Buddhists in Saigon decided to establish the Inter-party Committee to Protest Buddhism (abbreviated as the “Inter-party”), confirming a drawn-out struggle. Venerable Tri Quang sat on the Advisory Board, while Venerable Quang Do worked as assistant to the public relations committee of the Inter-party.

The objective of the Inter-party was to get the government to respond to five demands: withdraw the decree banning the flying of Buddhist flags, put Buddhism on equal footing with Catholicism, end the suppression of Buddhist followers, grant Buddhist monks and nuns the freedom to proselytize, and compensate for the deaths caused (during the crisis) and punish those responsible.

In the two days following the incident at the Hue radio station, Buddhists protested spontaneously, but thereafter, they gained a sense of order and organization with Venerable Tri Quang’s direction, the monk recounted in an autobiographical short story. He also found ways for Buddhists to come to Tu Dam Temple to pray each week for those who had passed away. In Saigon, monks organized spiritual processions from one temple to the next, as well as protests and hunger strikes.

The government only ramped up its repression; many temples in Hue were blockaded, and monks and nuns were publicly attacked. It wasn’t until Venerable Thich Quang Duc, 73, immolated himself on June 11th, 1963 that the situation improved in any meaningful way. Tri Quang traveled from Hue to Saigon to enter into discussions with the government.

In the weeks and months that followed Venerable Quang Duc’s self-immolation, the Inter-party signed a joint communiqué with the government responding to Buddhism’s five demands. However, the government never implemented the communiqué, greatly angering monks, nuns, and the general population.

According to Thich Nhat Hanh, at the time he was in America campaigning for religious freedom and a cessation of war in his own homeland. He appeared on television, met journalists, translated materials detailing the human rights violations in Vietnam, and pushed international organizations, including the United Nations, to intervene in the increasingly volatile situation in South Vietnam.

As Thich Tri Quang relayed in his autobiography, on the morning of July 17, 1963, Venerable Quang Do was unable to deliver translated international press updates to Xa Loi Pagoda. That day, countless Buddhists poured into Giac Minh Temple, where the monks were on a hunger strike. These crowds quickly morphed into an enormous protest. As the Buddhist adherents tried to approach Giac Minh Temple, they were blocked by police. Venerable Quang Do was among them, directing the protests to struggle not only against the police barricade but for Buddhism itself. In his book History of the Vietnamese Buddhist Struggle, Monk Tue Giac writes that after 10 am that morning, the protests had devolved into a fighting match with police. Venerable Quang Do suffered a head injury, blood pouring down his face. Any Buddhist who had not been arrested by police returned to Giac Minh Temple, resisting as barbed wire fencing kept more than 600 monks, nuns, and adherents barricaded for 54 hours.

By August 20, 1963, Ngo Dinh Diem’s government was determined to restore order. A day after martial law was imposed, monks were arrested and adherents attacked. Venerable Quang Do was apprehended. Venerable Tri Quang went to the American Embassy to apply for amnesty.

From that point until President Ngo Dinh Diem’s assassination on November 2, 1963, the struggle raged between Buddhists, the Army, and international pressure.

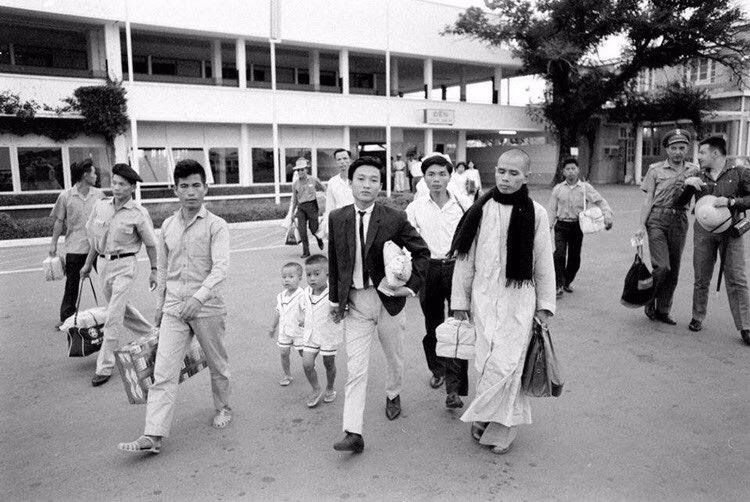

In December 1963, after the struggle had succeeded, Venerable Tri Quang along with other monks established the Unified Buddhist Church, Venerable Quang Do went overseas for medical treatment, and Venerable Nhat Hanh returned to Saigon.

While Venerable Tri Quang mobilized Buddhist adherents, monks, and nuns to continue the political struggle, Nhat Hanh was able to fulfill his wish of establishing several campuses, including the La Boi Publishing House, Van Hanh University, the Youth School for Social Services, and the Tiep Hien Congregation (a congregation centered on the full integration of Buddhism into daily life).

In May 1966, Thich Nhat Hanh headed to the US to campaign for an end to the war in Vietnam. After three months, the South Vietnamese government refused to let him return home. At the time, Thich Nhat Hanh began becoming world-renowned as the face for peace in Vietnam. The next year, Reverend Martin Luther King nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize.

At the beginning of 2005, as the people proudly and warmly greeted his arrival, Zen Master Nhat Hanh was finally able to return home after more than 40 years away, accompanied by a Sangha of approximately 200 adherents. He conducted talks with audiences that included party members in Ho Chi Minh City, Hue, and Hanoi.

Meanwhile, Venerable Quang Do lived in solitary confinement, locked in a room at Thanh Minh Zen Monastery in Ho Chi Minh City. Across the street were police whose only job was to keep an eye on him day and night.

During his trip, Zen Master Nhat was able to visit Venerable Tri Quang but not Venerable Quang Do.

In the eyes of the Vietnamese media, Zen Master Nhat Hanh was someone to be immensely proud of, he was “flesh and blood” who had returned to his homeland to further contribute to the people’s well being. Venerable Quang Do, on the other hand, was a boil that the government tried every means to remove. But back then, both monks were cut from the same cloth, up until the day Saigon fell.

After 1975, as Zen Master Nhat Hanh set up his Plum Village Monastery in France, Venerable Tri Quang was imprisoned for a year and a half in a hole the size of a coffin, which he was only allowed to leave for 15 minutes each day to wash up. From then on, people no longer saw him calling for protests or making demands for Buddhism; the international media was never able to make direct contact with him again for as long as he lived.

After the war, Venerable Quang Do along with a number of other monks fought for those who had self-immolated in the name of religious freedom and in protest of the new regime’s intention to eliminate the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam. In a country with no international media, no independent courts, and no freedom of association, these efforts would be in vain, the number of immolated corpses perhaps outnumbering that of the old regime. He was never able to reach a compromise with the government, up until the day he died.

Long ago, there lived three monks: Nhat Hanh, Tri Quang, and Quang Do. When the communists arrived, the lives of these three diverged completely.

Correction (April 12, 2020): in a version of this article, we had written that Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh had entered the monastery at Tu Dam Temple. We wish to correct this to Tu Hieu Temple, in Hue.

Footnote:

[1] See numbers 2 to 28 in Buddhism Magazine, and Intention’s Road Home (Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh).

References:

This article was written by Tran Phuong and published by Luat Khoat magazine on April 12, 2020. It was translated by Will A. Nguyen.

Vietnam's independent news and analyses, right in your inbox.