Việt Nam Slashes Use of Death Penalty: Eight Crimes Removed, Including Corruption and Drug Offenses

Key Events * Việt Nam Abolishes Death Penalty for Corruption Amid Wave of High-Profile Trials * Chinese Survey Ship Operates Near Việt

April 30, 2018|I’ve always been into the idea of counterparts—“separate but equal”, to borrow the politically dangerous phrase. Captain Planet, Sailor Moon, The Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers—these shows were always particular favourites of mine as a child because each contained an episode or arc where analogues to the good guys arose: Captain Pollution and his team of toxic “planeteers”, the Four Sisters of the Black Moon, or the Dark Rangers. I find the inherent sense of balance in counterparts intensely satisfying, like yin-yang writ large.

As I’ve grown older, this affinity for correlates extended to international politics, in particular, ideologically-opposed, directionally-split countries, i.e. North and South Korea, or East and West Germany.

The time when the modern Vietnamese nation-state existed as two separate entities naturally possesses a particular gravity in my mind, as I’m sure it does in the minds of many overseas Vietnamese. After all, that pair’s existence, its mutual antagonism, and one’s annihilation of the other is single-handedly responsible for the dispersal of Vietnamese people across the globe, a burst of human photons in one of many collisions between communism and anti-communism.

I was born in America; unbeknownst to me at the time, all the Vietnamese I ever encountered were former citizens of the Republic of Vietnam (i.e. South Vietnam) or as I’d known it, Vietnam. There was no alternative, no other. The yellow flag with three red stripes were ubiquitous and the only representation of Vietnam I knew.

Encarta Encyclopedia 97 provided me the first hint of another truth, of another “Vietnam” – the “evil” one, I would quickly learn. I remember doing a project in fifth grade which required us to produce a “country profile” on a nation of our choosing. I referred to the CD-ROM encyclopedia and, without giving it much thought, copied out the red flag with yellow star, Vietnam’s official flag as listed within the country’s entry.

My grandmother was the first to “correct” me, scolding me as Encarta played “Tiến Quân Ca”, the national anthem of North Vietnam from 1945-1975, and after the war, the official one of all Vietnam. That was not the “real” anthem, she told me. The information in that article was “wrong”. When I asked her what the real anthem was, she hummed “Tiếng Gọi Công Dân” – the national anthem of South Vietnam from 1948–1975 – a tune I was much more familiar with.

As I finished up my project, I asked my mother to look over my work. What she did, whether intentional or not, resounds with me to this day. Rather than make me remove my drawing of the yellow-starred red flag, she had me draw South Vietnam’s red-striped yellow flag next to it, presenting both flags as equally valid.

It took me at least another two decades to realise this, but my mother’s simple gesture was both an extremely powerful teaching moment and a representation of my intellectual angst with the overseas Vietnamese identity. It was my first taste of the concept of contradictory but co-existing truths.

Growing up, I never gave that distant land of Vietnam too much thought; the framework for that place and its people had been set up for me. We (the southerners) were the good guys; they (the northerners) were the bad. Everything we said was true; everything they said was lies. I never wondered why we were the ones living in another country.

College, membership in an active Vietnamese student association, and a kind-hearted Vietnamese professor ushered in a new era of knowledge for me. I began taking my first steps toward balance, and further steps towards the truth… or rather, truths.

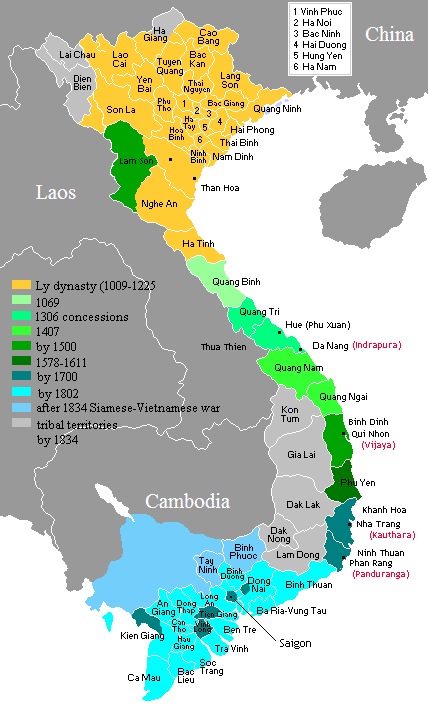

In Vietnam, “nam tiến”, literally meaning “march to the south”, refers to the expansion of Vietnam southwards, from the Red River Delta down to the Mekong River Delta. This development shapes Vietnam’s long-standing stereotypes between northerners and southerners. Contrary to people who like to compare the shape of Vietnam to a bamboo yoke or the letter ‘S’, I like to think of the state in more metaphysical terms: a past-oriented north that flows to a future-oriented south.

The Red River Delta is held up as the “birthplace” of Vietnam, the traditional seat of culture and politics. The northern region and its people are perceived as conservative, ascetic, and prone to resource and food shortages. This has bred a northern character that prizes resilience, indirect communication, the concept of “face” (linked to the concept of one’s honour and prestige), and a muted cuisine that uses fewer herbs and spices.

As the state advanced into Cham and Khmer territory, a separate centre of power began developing in the south, attracting those drawn to “frontier” life and a multi-cultured existence. By virtue of self-selection, Vietnam’s expansion south drew the free-wheeling, the forward-looking, the liberal, the cosmopolitan. The south was more abundant in food and resources; Saigon – formerly known by its Khmer name Prey Nokor and currently by its Sino-Vietnamese name Ho Chi Minh City – drew traders from the world over, and life was on the whole, easier and more prosperous.

These historical circumstances have defined what it means to be a southerner: we speak with a relaxed drawl and in a straightforward manner, we cook flavourful, vivacious, eclectic dishes, and we possess a progressive, open outlook that embraces global trends. It was no surprise that the south Vietnamese eagerly adopted American dress, customs, and culture during the 1950s – 1970s.

But it isn’t just a matter of character traits and cuisine; regionalism in its extreme form has repeatedly led to Vietnamese killing Vietnamese. Historian Huy Duc describes Vietnam as a home “whose walls are made of flesh and blood”. It’s not just a metaphor.

A civil war in the 17th century proved to be an eerie foreshadowing of events three centuries later. The north and the south were split into two separate polities: “Đàng Ngoài” and “Đàng Trong”, literally the “outside” and the “inside”. The Trinh lords ruled over the north, the Nguyen lords the south. In 1802, the southern Nguyen lords ultimately triumphed over their northern Trinh rivals, uniting the country under its Southern aegis. Inklings of this contentious period still remain in our language: to this day, Vietnamese still say they are going “out” to Hanoi and “into” Saigon.

The 20th-century civil war between North and South was a reverse iteration. The 1954 Geneva Accords split Vietnam into directional counterparts once more – a communist north versus a democratic south – with nationwide elections set to unify the country in two years’ time. Ho Chi Minh was predicted to win. Knowing this, Ngo Dinh Diem declared the formation of an independent southern republic that technically was not signatory to the Geneva Accords and thus un-beholden. The United States supported the non-communist South Vietnamese government, pouring in financial aid. The northern victory in the Vietnam War in 1975 unified the country once more, but different perspectives persist. Depending on who you talk to, 30 April 1975 – the day the People’s Army of Vietnam and the Viet Cong captured Saigon – is described either as a liberation or an invasion.

Depending on who you talk to, 30 April 1975 is described either as a liberation or an invasion

My mother regularly reminds me I’m from the south. When I first began taking Vietnamese language classes in college and started pronouncing my v’s, qu’s, and final consonant n’s, she and my eldest aunt jested that I’d “become a northerner”. In class, I quickly learned that much of the Vietnamese I spoke at home was heavily marked by southern vocabulary used pre-1975. The enormous amount of South Vietnamese who had transplanted themselves in the 1970s and 1980s had led to the creation of communities that were essentially living time capsules.

The southernness of my spoken Vietnamese comes and goes depending on how inebriated I am, but the pride is palpable. On the first day of my advanced Vietnamese class at the College of Humanities and Social Sciences in Ho Chi Minh City in 2012, the professor asked me where I was from – “Will là người gì?”

Without thinking, I responded, “Will là người nam (I’m a Southerner).”

Taken aback but pleasantly surprised, the professor said that, in her 30 years of teaching, she’d never heard such a response from a “foreign-born”. I quickly corrected myself – “Will là người Mỹ gốc Việt (I’m a Vietnamese-American)” – but the identity ambiguity persists.

My investigation of the history between the north and south often involved prodding fellow southerners with sensitive topics. Once, I asked my Vietnamese professor in college in the United States about one of the war’s alternate names in Vietnam – “Chiến tranh chống Mỹ cứu nước (The war to resist America and save the nation)” – which heavily implied that we southern Vietnamese were imperialist collaborators. (For the record, the first South Vietnamese president, Ngo Dinh Diem, and his brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, were both assassinated with tacit American support for not being compliant enough.) It was a mind-blowing experience to later see the phrase in propaganda posters on the streets of Saigon.

I had, of course, to thoroughly research the other side as well; I read numerous books and watched countless interviews from individuals on the Communist side, both those based in Hanoi as well as those hidden away in the jungles of South Vietnam.

On my first trip to Vietnam in the summer of 2007, I took liberties during my research project on gay culture in Saigon to randomly ask locals their thoughts on the war, on life post-1975, on their current government.

“These colorful billboards… on every corner. They’re so strange, aren’t they?” That was how I broached the topic with the motorcycle drivers. Casual. Open-ended. The propaganda signs, with their blocky, solid-colored, Soviet-style imagery, were a genuine curiosity to me. They were government-sanctioned, overtly political signs, exalting the Communist Party’s leadership in history, in the South’s “liberation”, in developing a “modern”, civilised Vietnam. And they were literally everywhere. As we drove by the myriad signs peppered around the city, I would use the occasion to ask the moto-drivers their opinions of the political status quo.

“They’re a bunch of liars.”

“They don’t really care about the people.”

As one driver zoomed past a particularly large mansion, he told me that it was the residence of a prominent Communist Party member. There was a consistent sense of cynicism among these working class motorists.

An older, southern woman’s story was particularly interesting, as she was old enough to have experienced the “liberation” and the years that followed. I met her through a family friend of my mother’s. (My mother had been terrified for my safety; I was the first family member to return to Vietnam since they fled, and I would be traveling completely alone as the child of a “collaborating” family.)

Upon arriving at the house, I was impressed by how large and modern it was. It had granite countertops, hardwood floors, and classic, imposing cherrywood furniture. This was luxury by Vietnamese standards; with at least four motorcycles sitting in the spacious courtyard, it was clear this family was relatively well off.

Auntie and I were sitting in the living room having a casual chat about our families, when the conversation turned to what life was like immediately after 30 April 1975.

At this point, she got up to close all the doors and windows, drawing the curtains. She whispered for the rest of the conversation. Her family had been businesspeople during the Republican era, accumulating a good deal of wealth. After the Communists came to town, local party members, aware of the family’s affluence, found an excuse to confiscate the house. It was impossible to dispute the move, so the family decided to work within the new system, establishing enough political connections to eventually reclaim the house within a decade or so. There was a healthy dose of disdain for the powers-that-be in her stories, but her family’s resilience, tenacity, and resourcefulness overshadowed all else for me. It was an injustice corrected through cunning manipulation of an alien political system. That she was still paranoid about being overheard 20 years later speaks volumes of the pervasive and oppressive surveillance state the Vietnamese live under.

A different perspective came in the form of a Northern shopkeep at a propaganda poster shop. She’d noticed my many visits to her shop, and figuring out that I was Việt Kiều (overseas Vietnamese), took the initiative to engage me in conversation about history and politics.

I was taken aback but excited by her friendliness and eagerness to help me understand Vietnam. She told me to ask her anything I wanted. Aware that I was part of a Southern family that had fled after the war, she knew I’d been served a healthy dose of skepticism regarding Communism and the current political regime, and tried her best to argue for the other side. She’d moved to Ho Chi Minh City, she said, after its liberation.

“When you work against the victors, you are naturally apprehensive when they arrive”

I got straight to the prickly issues. Why had so many people from the South fled? What of the re-education camps? How can the powers-that-be call the current system “democratic” when there’s only one party in charge?

“People fled because they feared retribution,” she said. “When you work against the victors, you are naturally apprehensive when they arrive.”

The re-education camps, she went to on say, were not all that bad: “The ones I visited even had nice gardens and flower beds. And in any case, you have to understand the situation that the new government was in. You had an entire population grow up under an enemy’s regime. When you come to power, you have to make sure this group cooperates, you have to make sure this group is educated in the ways of the new regime.”

Her answers started to waver, though, when it came to the current “democratic” system. “We have elections. We have voting. We have representatives who form a national assembly,” she said.

“Yeah, but all that stuff doesn’t really matter when you can only pick representatives from one party,” I argued back. “If everyone is forced to follow the same ideology, the same ideas, choice is a moot point. True democracy involves multiple parties.” She disagreed, insisting that because the organs existed, democracy existed in Vietnam.

To be sure, truth is a sensitive topic on both sides; I’d had just grown up entrenched in the anti-communist camp rather than the anti-capitalist one. Various attempts to remedy the situation have led to some rather awkward moments. I remember a conversation between my aunt and my mother where my mother said she had to give credit to the Communist government for keeping the country together and growing the economy at an appreciable clip, but my aunt quickly retorted that my uncle – who had served in the South Vietnamese army – would have maimed her if he heard her talking like that.

I’m still researching today, adopting a less polarised, more nuanced approach to the war and its competing ideologies than perhaps my mother would like. During a BBC interview, southerner Nguyen Thi Binh, former foreign minister of the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam and prominent Communist figure at the Paris Peace Accords, was asked for her thoughts on Vietnamese dissidents and their desire for a better nation. She retorted: “How are they any different from me?”

The dichotomy of “good versus evil” had been so deeply ingrained in the narratives of north and south that, until I heard that comment, I’d never really thought of it that way. These people, these Communists, laid down their lives for their ideals, for their country, and perhaps most meaningfully, for their countrymen. Can, or should, we cynically believe that those who fought on the northern side sacrificed the spring of their lives, and sometimes their lives altogether, simply to gain power at the expense of their fellow Vietnamese?

What, on the other hand, was the South fighting for? Trudging through American history books, one would be hard-pressed to find any real, fleshed-out answer beyond “the domino theory”, a theory that argued that the fall of one country to Communism would lead to a domino effect among its neighbours. Reading such material, it was hard not to buy into the (Hanoian) idea that South Vietnam was a propped-up American creation. In fact, the more I researched, the more I realised that it was a deep sense of ambivalence among the southern population that lead to South Vietnam’s embarrassingly quick demise.

When asked why they were fighting and what they were fighting for, South Vietnamese soldiers often turned out not to be very firm believers in their own cause. Boots and uniforms stripped off and abandoned in place by soldiers deserting on 30 April 1975 testify to that fact.

The wartime South Vietnamese population might not have been able to answer the question of “what are we fighting for?”, but the next few decades of economic mismanagement and political oppression after unification would provide a resounding answer, especially for those not able to escape the country.

By the early 2010s, after nearly a decade of research and reading, my viewpoint had matured from “acknowledge that our side may have been ‘wrong’, and then find out what happened on both sides” to “never lose sight of the fact that democracy as the South attempted to espouse it trumps the totalitarian communism adopted by the North.” Both were foreign, imposed ideologies, and the fact that one conquered the other has no bearing on virtue. As the Vietnamese author and political dissident Duong Thu Huong so eloquently put it: “Beauty does not always triumph.”

Though film and media are thoroughly dominated by northerners, southern defiance is coming to the surface. “We only learn how to cherish things when we’ve already lost them,” the 2017 trailer of Cô Ba Sài Gòn (The Tailor) begins. The southern voiceover is immediately followed by a close-up of Saigon’s city hall, with the camera focused squarely on the flagpole – there the flag of South Vietnam flutters. Yellow with three red stripes. It is subtle but perceivable for those who look for it.

But of course, if that is too subtle for you, you can always rewind a few seconds and there staring you in the face from the very moment the trailer starts is the flag on the áo dài. The tailor’s hand gently caresses a swath of yellow with three red stripes. Genuinely ask yourself if this is all coincidence. Of all the patterns in the world that the filmmakers could have featured on the dress, why this one? And why does the voiceover make the statements she does as this pattern is displayed?

A slow zoom-out, followed by shots of economic prosperity and vibrant displays of traditional áo dài to emphasise the blossoming of Vietnamese culture under a “fascist”, “puppet” regime. That these scenes managed to make it onto the big screen directly undermines the communist narrative of Saigon needing to be “liberated”. A particularly salient question asked among dissidents, both in and outside the country, is “who liberated whom?” Did the impoverished North really liberate the wealthier South? Or was it the other way around? Moreover, what exactly did the South need liberating from? A comfortable, prosperous, peaceful life?

The film champions the preservation of the áo dài – the traditional Vietnamese outfit – over Western fashions in 1960s Saigon, but the subversive message, wrapped in the garb of an innocent movie about fashion, is unmistakable. For South Vietnam, the loss is more political than cultural: no longer do citizens possess freedom, democracy, and a vibrant civil society. Even if imperfectly practised in South Vietnam, greater freedom of expression brought prosperity and a society of better quality than what Vietnam has today. Many Vietnamese, unable to express dissatisfaction with the status quo at the ballot box, vote with their feet. Leaving the country is the dream for those who have means to do so; Hanoi readily acknowledges that Vietnam suffers from brain drain.

Even so, it must be acknowledged that the war was a manifestation of North and South both wanting the best for the Vietnamese people while choosing drastically different paths. It would be unforgivably cynical to believe otherwise, to view either government as monolithic entities not made of Vietnamese individuals who loved their country. The root of the conflict stemmed from both sides competing to be the only good. Both the North and the South had causes they believed to be just – a fact which native and overseas Vietnamese have yet to fully accept.

On paper and in diplomatic circles, there is only one “true” Vietnam. Although the Republic of Vietnam ceased to exist after 30 April 1975, it lives on in the hearts and minds of millions of Vietnamese who abhor communist totalitarianism. It lives on in its enforced absence within Vietnam’s national discourse. A silent, de facto ban of the yellow flag with three red stripes, of any positive mention of the southern republic, of anything related to the former state is, in a way, perpetuating South Vietnam’s existence. And if history is any indication, the South remembers.

About the Author:

|

Vietnam's independent news and analyses, right in your inbox.